You are no doubt aware of the need to keep an invention secret before a patent application is filed, but there are also circumstances where disclosures relating to your invention made after a first patent application has been filed can potentially jeopardise further protection for your invention. You will probably want to publicise your invention after a first application has been filed and whilst this is usually possible and indeed commonplace, there are circumstances where a disclosure of your invention, or of ideas or improvements relating to your invention, may limit your options for filing further patent applications. In particular, there can be legal problems if you intend to further develop the invention and to file additional patent applications either in this country or abroad. This page aims to explain how these problems can arise and how they can be avoided.

In brief

What you can and cannot disclose will depend on the patenting strategy for protecting your invention. Since it is not always possible to be certain when or where future patent applications may be filed, it is likely that there will always be some risk that a public disclosure may jeopardise the patentability of a future application. Therefore, the decision on whether to disclose or not will probably turn on where the level of acceptable risk lies. In any event, if you decide to publicise your invention you should not talk about anything that has not been included in the first patent application unless you are certain that you will not want patent protection for that additional subject matter.

In addition to the points discussed in detail below, there are some important general points to bear in mind when making your decision:

Any disclosure you make of the subject matter contained in the first application will not count against the first application if and when it comes to be examined.

However, a disclosure of the subject matter in the first application may prejudice the patentability of any other application filed subsequently for the same invention (without claiming priority, see below) or a related invention, for example one that relies on the same underlying principles or discoveries contained in the first application.

Furthermore, any disclosure of subject matter not contained in the first application (e.g. improvements or new results) may prejudice the patentability of a future application directed to that subject matter.

Sometimes it is desirable to withdraw a first application before it is published and re-file it at a later date, for example to delay the costs of filing an international application, or for tactical reasons. This approach would not be successful (in the UK and Europe at least) if you disclose the subject matter of the first invention before the application is re-filed.

What is the "normal" approach to patent protection?

As a rule, once an invention has been made a first patent application is filed. For UK companies and clients this will usually be done at the UK Intellectual Property Office. It is common for work then to continue on the invention and for improvements to be made. Further patent applications can be filed to "add" these improvements to the first application, usually as long as this is done within 12 months of the first application.

Generally towards the end of the 12 months a new "final" application will be filed to consolidate the previous application(s) and any improvements to the invention. Under certain conditions, this new application can be "backdated" as if it had been filed at the same time as the first application. However, as will be explained below, these conditions may not always be met and the backdating effect not obtained. This is what can cause problems if the invention has already been publicised even after the first application was filed.

Also within these first 12 months it is possible to file "final" applications in most countries and, again under certain conditions, to backdate these new applications as if they had been filed at the same time as the first application. Usually this will be done towards the end of the 12 month period in order to defer costs but again if the conditions are not met then problems can arise if any details of the invention have been made public.

What is the significance of the filing date and the priority date?

Every patent application will have a filing date, i.e. the date on which it was filed. If the application is backdated (i.e. the conditions are met) as explained above, then it will also have one or more "priority" dates which are the filing date(s) of the earlier application(s).

For a patent to be granted, the invention must be new and inventive with regard to the technical information already in the public domain at the filing date. If the application has a priority date then this acts as the filing date for this purpose.

Example:

A) Application X for invention A filed on 6 January 2008 in the UK.

Novelty and inventiveness will be judged against information available to the public at filing date of 6 January 2008.

Filing date = 6 January 2008

B) Final application(s) Y for invention A filed on 4 January 2009 for example in the UK, USA and European Patent Offices.

Although these applications were not filed until 2009, they were filed within the allowable 12 month period and may therefore be entitled (if the conditions explained below are met) to the priority date of 6 January 2008 at which to judge the novelty and inventiveness of the invention.

Priority date = 6 January 2008; Filing date = 4 January 2009 Application X = "priority application".

What if the final patent application(s) contain more information than the priority application?

As mentioned above, this is very often the case. The legal question which has to be answered is whether or not the information which has been added is entitled to be backdated to the date of the priority application.

If the final application has a claim which relates in whole or part to the added material then this question can become very important.

The answer to this question can differ from country to country and depends on the law of each country in which the final application(s) have been filed.

Below we will explain how the question is answered in the UK and at the European Patent Office according to current case law. The most relevant EPO case is G3/93.

Is the new material entitled to the earlier priority date?

The simple answer is that almost certainly any significant new material will not be entitled to the priority date.

The case law is complex and sometimes conflicting, but only if the new material is relatively trivial will there be a chance of it benefiting from the priority date.

Therefore, the extra information present in the final application will have a corresponding later filing date than that attributed to the information contained in the priority application. Thus, the patentability of the extra information will be judged against the more extensive published information available up until this later date, including any publication of the invention by you.

What is intervening publication?

It is a publication of all or part of the information contained within the patent application in the period between the priority date and the filing date of the patent application whether by you or by a competitor.

This therefore includes a publication by you of all or part of your invention.

What is the effect of an intervening publication?

This is best explained by way of an example.

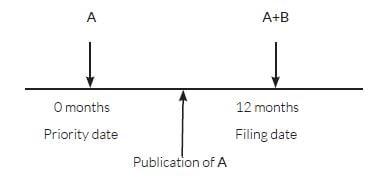

Consider the scenario where a patent application is filed (at 0 months) for an invention, the subject matter of which is A. Shortly after, the subject matter of A is published. During the 12 months after filing the application, more work is done and an improvement is made (B). A final consolidated application is filed at the 12 months date which claims the "priority date" of the earlier application.

If the final consolidated application contains the following claims:

1. A inventive concept 1

2. A+B inventive concept 2

then:

- Claim 1 will be entitled to the earlier "priority date" and the intervening publication of A will not matter as it was not available to the public before that date.

- Claim 2 will not be entitled to the earlier "priority date" as the concept of A+B was not disclosed in the priority application. In this case the intervening publication forms part of the "prior art" and claim 2 must be both new and inventive with respect to it.

- Clearly, the publication does not disclose all of A+B as it does not contain the extra material B and so claim 2 will still be new. However, the teaching contained within the publication may mean that A+B is obvious and therefore unpatentable due to lack of inventive step.

Thus the publication of A can cause serious problems for at least a part of the final application.

In real life the situation is rarely as clear cut, as A and B may not be so distinct from each other. It is possible for example that the priority application may mention B but may not include enough relevant technical information about it - perhaps the information was not available as at that time B was still being developed or investigated. Generally the rule is that enough technical information must be present to allow a "skilled person" to understand and carry out the invention. In another case, perhaps A is a particular example of the invention which is known to work and B is an expanded class of examples which are believed to work but you were not sure at the time.

In both cases, A+B is still not entitled to the priority date as B is said not to be "enabled" in the priority application, despite being mentioned.

What should I do?

If further pertinent work is to be carried over the 12 months following the first filing of a patent application, then this work should be made the subject of a second or subsequent consolidated application BEFORE ANYTHING is published.

There is no absolute requirement to wait the full 12 months before filing any subsequent application if significant work in the project is completed before that date, and often it is desirable to file a subsequent application sooner.

If at all possible, it is preferable to avoid publishing any information about the invention until all "final" applications have been filed.

This information is simplified and must not be taken as a definitive statement of the law or practice.

Topics:

Our people

Our IP specialists work at all stage of the IP life cycle and provide strategic advice about patent, trade mark and registered designs, as well as any IP-related disputes and legal and commercial requirements.

Our peopleNews & Insights

Read our blogs to keep up to date with developments in the IP world and what we are up to at Mewburn Ellis.

Contact Us

We have an easily-accessible office in central London, as well as a number of regional offices throughout the UK and an office in Munich, Germany. We’d love to hear from you, so please get in touch.

Get in touch