The Volta Foundation have recently released the 2024 edition of their annual Battery Report. These reports are well-renowned in the industry and cover the most important developments in battery research, policy and business landscape. We at Mewburn Ellis were delighted to participate in this year’s report, as Mewburn Ellis partner Callum McGuinn contributed an analysis of the battery patent landscape.

In this fourth instalment of our series looking at the 2024 Battery Report, we explore the continued development of the ever-promising sodium-ion (Na-ion) battery market. A recent study in Nature, modelling the future sodium-ion supply chain, explains that the technology “deserves considerable research, development and commercialization attention”.

A Well-Seasoned Year

As the Battery Report highlights, 2024 was a year in which plenty of progress was made in the development and application of sodium-ion battery technology. For example, as we mentioned in a previous instalment of this series, the first phase of the world’s largest sodium-ion battery energy storage system (BESS) by the Datang Group is now in operation in China, and another was announced by BYD at the end of the year.

The sodium-ion electric vehicle (EV) market also saw huge advances in 2024, with innovators such as Farasis and JMEV, JAC, and CATL unveiling cars powered by their respective Na-ion batteries. But the EV advances aren’t limited to cars: TAILG has revealed sodium-ion e-bikes, while Komatsu has developed a 1.5-ton electric forklift powered by a sodium-ion battery.

Although the above companies are all located in the Asia-Pacific region, recent developments in Europe and the United States suggest that the potential of sodium-ion is globally recognised. Dutch automotive manufacturer, Stellantis, has invested in France-based sodium-ion innovator, Tiamat, to help bring the technology to the European market. On the other side of the Atlantic, Natron Energy has announced its plans for a $1.4 billion giga-scale sodium-ion battery manufacturing facility in North Carolina. Meanwhile, the US Department of Energy awarded US$50 million to establish a Na-ion storage consortium, led by the Argonne National Laboratory.

A Surplus of Sodium

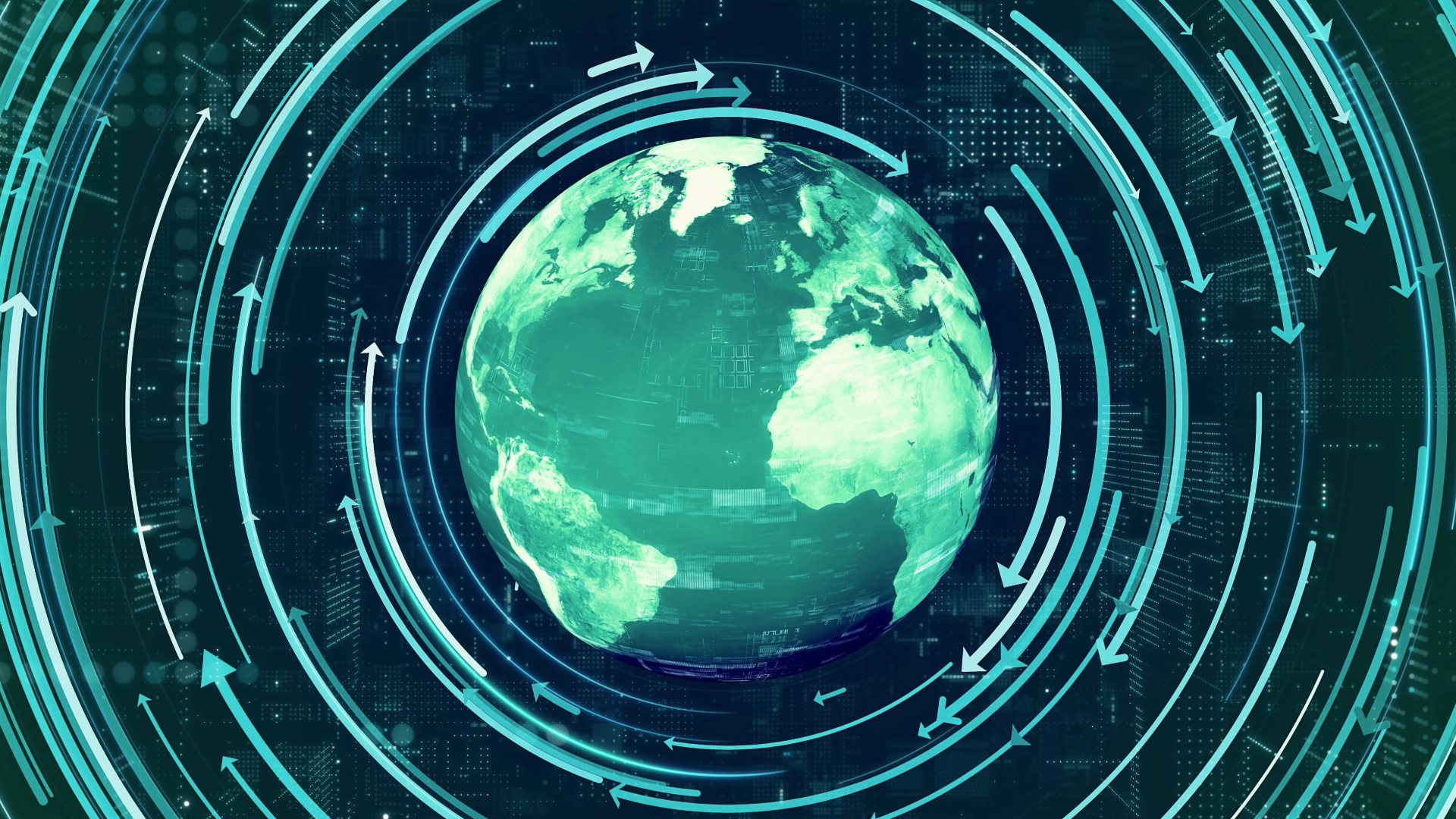

The Battery Report indicates that there is over 1700 times as much recoverable sodium globally compared to lithium (an estimated 26 billion tons of sodium compared to lithium’s 15 million tons).

Sodium’s natural abundance is one of the key factors which contributes to its potential value in energy storage devices. While the so-called “Lithium Triangle” of Bolivia, Argentina and Chile hold over 50% of the world’s lithium reserves, the lack of developed mining and refinery infrastructure mean that Australia and China lead in lithium production. In contrast, the USA holds over 90% of the world’s sodium mineral reserves, which are largely made up of soda ash (Na2CO3), which is a raw commodity with an existing processing framework.

The below graphic from page 278 of the 2024 Battery Report illustrates the geographical location of raw sodium and lithium supplies:

The availability and processability of raw sodium material translates to the potential to achieve prices of less than US$40 per kWh at scale. Further bringing down costs is the fact that sodium-ion batteries can be manufactured using identical methods to lithium equivalents, which means immediate scalability is possible. The vast abundance of sodium could be key to addressing long-term battery supply chain challenges, and provide an avenue through which China’s global dominance of lithium refining could be traversed.

In addition to cost, sodium-ion cells boast several other advantages over existing lithium technologies. For example, they allow for operation at much lower temperatures (as low as −40 °C), safe zero-voltage storage and transport, and rapid charging. Additionally, the Battery Report shows promising properties of various sodium cathode materials. For example, Na-ion layered oxide materials have been shown to have high energy density and similar thermal runaway properties to Li-ion layered oxides, while Na-ion polyanion cathodes have been shown to avoid thermal runaway completely.

Looking Forward with a Pinch of Salt

Despite the huge recent progress and promise of safe, cheap and abundant battery materials, the widespread adoption of Na-ion technology still faces significant challenges which must be overcome with research and investment.

In general, a sodium-ion battery is still outperformed by a lithium-ion equivalent in terms of energy density and voltage ranges. There is also some uncertainty around the bold safety claims of this relatively young technology. And despite the clear potential for the raw material to lead to reduced costs, the set-up and R&D costs in the early stages still place a limitation on the potential economic benefits at present, as is common with emerging technologies.

Nevertheless, with such potential in this market, it is no surprise that innovators are taking steps to protect their intellectual property. As we reported in our previous article on Na-ion batteries, we have seen a clear increase in patent applications in this field in recent years (which are a useful indicator of trends in technological developments):

The number of international (PCT) patent applications published from 2008-2023, related to Na-ion batteries1

Based on the patent figures and the need to overcome the current challenges, we therefore expect that innovation and commercialisation of Na-ion batteries will continue to grow in 2025 and beyond, driven by sensible and strategic IP considerations. With our knowledge and experience in battery technology, the Mewburn Ellis energy storage team understand the importance of a strong IP position and are well equipped to provide support and advice – so do feel free to get in touch with us!

Read the full Battery Report 2024 series here.

1Search conducted for WO publications on Espacenet with (“sodium-ion” OR “Na-ion” OR “sodium ion” OR “Na ion”) AND (“battery” OR “secondary cell” OR “batteries”) in the title or abstract, and categorised as IPC main group H01M10 (“Secondary cells; Manufacture thereof”).

Matt is a trainee patent attorney in our chemistry team. Matt has a BSc and MChem in Chemistry and Mathematics (Joint Honours) from the University of Leeds. His Master’s research project involved the synthesis and characterisation of metal-organic frameworks incorporated into polymer films which have potential for use in hydrogen fuel cells. Matt also carried out a summer research project funded by the Royal Society of Chemistry which utilised computational chemistry to model reactions in the interstellar medium.

Email: matthew.barton@mewburn.com

Sign up to our newsletter: Forward - news, insights and features

Our people

Our IP specialists work at all stage of the IP life cycle and provide strategic advice about patent, trade mark and registered designs, as well as any IP-related disputes and legal and commercial requirements.

Our peopleContact Us

We have an easily-accessible office in central London, as well as a number of regional offices throughout the UK and an office in Munich, Germany. We’d love to hear from you, so please get in touch.

Get in touch