Collaboration is ubiquitous with successful research. Sharing results generates new leads, sharing problems inspires new solutions, and sharing proceeds funds new research.

In part, the increasing number of collaborations is down to advances in information technology, communication, and knowledge sharing. However, another key factor is that research fields are becoming more multifaceted and interrelated, while researchers are simultaneously becoming more specialised. More than ever, research needs collaborations to flourish.

By way of example, during the course of the 20th century less than one third of the Nobel prizes for chemistry were awarded to collaborating researchers. In contrast, 17 of the 20 chemistry Nobel prizes this century have gone to a collaborating duo or trio.

Polymer chemistry, in particular, spearheaded the collaborative culture that is now pervasive throughout scientific study.

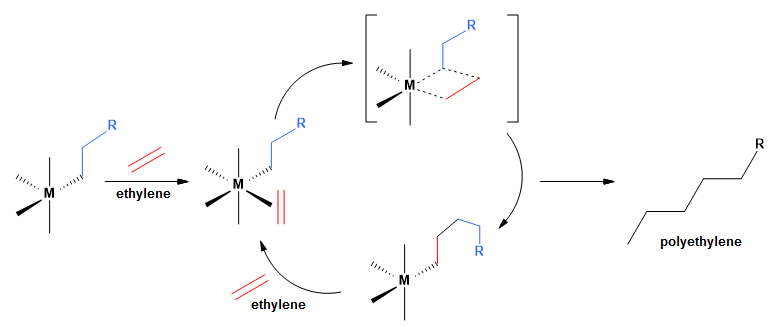

A pioneering case is that of Karl Ziegler and Giulio Natta. In 1963, their work on Ziegler-Natta catalysis was recognised for its impact on the manufacture of modern plastics, and is still a mainstay of polyethylene manufacture today.

Ziegler-Natta catalysis was the first process to yield high molecular weight polyethylene at low pressures and temperatures. This not only reduced cost, but gave stronger, higher density plastics by virtue of the limited branching and more crystalline molecular structure that was achieved.

Their further work on catalyst structures enabled stereochemical selectivity to be achieved in industrial scale manufacturing. This transformed the customisability of plastic’s properties and ignited an explosion in its applications, dawning the era of “everyday plastics” which is only now beginning to wane.

A polymer revolution

At the turn of the millennium another prize winning polymer revolution was brewing, this time in conductive polymers.

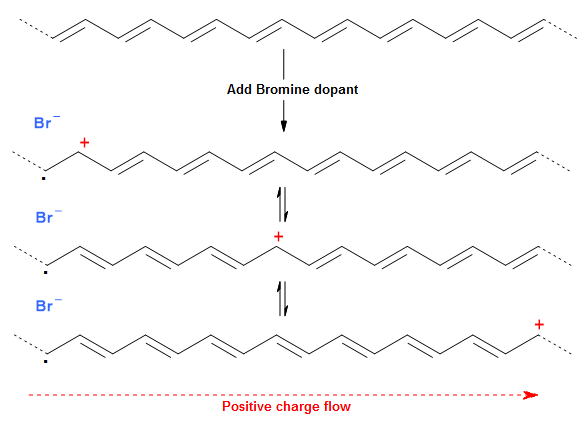

Traditional organic polymers are the antithesis of conductive. However, Alan Heeger, Alan MacDiarmid and Hideki Shirakawa developed polymeric architectures with remarkably high conductivity. Taking inspiration from doping methods commonly used in semiconductors, MacDiarmid and Heeger doped sulfur nitrile polymers with bromine atoms to induce a 10 fold increase in conductivity. Doping with bromine removes an electron from the polymer strand, leaving a positive ‘hole’ to shuttle down the length of the polymer and transfer charge like a molecular wire.

A similar approach was later applied to polyethyne, which has an electronic structure analogous to sulfur nitrile, but benefits from better flexibility and durability. However, polyethyne demonstrates a 106 conductivity increase over its undoped analogue (opposed to only 10 fold for sulfur nitrile).

Extensive applications were found for these new conductors, from transistors to plastic batteries, making new conductive polymer designs highly valuable. Heeger, for example, founded numerous spin-out companies leveraging the technology. One such spin-out focusing on polymer LEDs was subsequently purchased by DuPont and another, Konarka, sought to develop printable photovoltaic solar cells.

The importance of determining ownership

Clearly these prize-winning innovations represent only a tiny fraction of successful research collaborations in the polymer field, let alone across all research areas. The total commercial value vesting in collaborative innovation is understandably huge and collaboration agreements with strong IP provision can be hugely beneficial to collaborative partnerships.

That said, in order to realise the potential value, it is essential to take account of the intellectual property nuances associated with collaborative inventions. Inventorship, ownership, entitlement and benefit need to be considered early on in the patent application process. The often complex inter-relations between organisations, especially in cross-border arrangements, can bring particular challenges so it is generally easier to sort out the chain of ownership and any possible ownership issues sooner rather than later as relevant evidence may have been lost or forgotten over time.

The Mewburn Ellis legal team has extensive experience drafting and advising on IP agreements. They can support all IP transaction needs, including advising on strategy and deal planning as well as preparing, reviewing and negotiating contracts. All advice and support is given with a high degree of commercial understanding and is designed to ensure the best possible outcome in any given deal.

Niles is a Patent Attorney working in the chemistry field. Niles has an MChem degree in chemistry from the University of Oxford. His undergraduate research project was on the synthesis of novel perylene diimide containing macrocycles for anion recognition and sensing applications.

Email: niles.beadman@mewburn.com

Sign up to our newsletter: Forward - news, insights and features

Our people

Our IP specialists work at all stage of the IP life cycle and provide strategic advice about patent, trade mark and registered designs, as well as any IP-related disputes and legal and commercial requirements.

Our peopleContact Us

We have an easily-accessible office in central London, as well as a number of regional offices throughout the UK and an office in Munich, Germany. We’d love to hear from you, so please get in touch.

Get in touch