You conduct due diligence of intellectual property (IP) rights to check what is being sold or licensed or offered as an investment. If a buyer does not conduct due diligence they will have to rely on the contractual warranties given by the seller (if any), because caveat emptor applies. If a seller does not conduct an IP audit they may be ill prepared for the sale, licensing or investment event.

IP basics

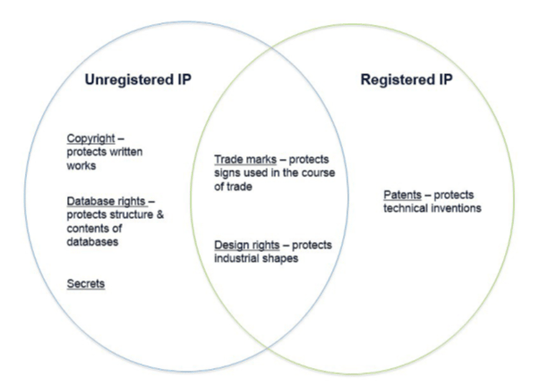

As a starting point you should remember that there are many different types of IP. Understanding the difference between them is essential to properly conduct due diligence.

IP falls into two general categories: registered and unregistered rights. Registration is essential to get some IP rights (patents), but optional in other cases (trade marks and designs) though registration makes it easier to enforce your rights. Registration also provides a priority date against later identical or similar registered rights. Unregistered rights arise automatically. They do not have to be applied for. However, with unregistered rights you have to demonstrate that the right exists and that you own the rights.

Figure 1: The general categories of intellectual property. ©Mewburn Ellis LLP 2016

The difference between buyer due diligence and seller audits

Due diligence can be conducted by both the seller and the buyer. A buyer wants to know that what they are buying is worth the price and that it will allow them to achieve their commercial objectives. They will also want to understand the risks. A buyer tends to conduct his due diligence once a transaction has started or is imminent.

In contrast a seller may want to check the status of their IP before it is offered up for sale or licence or investment. Some call this an “IP audit” rather than due diligence. The seller is looking to determine a value for their IP and to check for any “skeletons in the closet”. Doing so will help them to prepare for discussions regarding risk or price. A seller may also need to set up a data room to ensure that the right information about the IP is being disclosed (at the right time) to the buyer.

The investigation

The first stage of due diligence is for both a buyer and a seller is the investigation of the IP. A buyer will tend to do this once the transaction is seriously contemplated. A seller can, however, conduct their audit at any time. In fact, there are many advantages to conducting it as early as possible or at regular intervals. Doing so will remove the time pressure on the seller, allowing them, for example, to take appropriate corrective actions or get their valuation reasoning straight.

Some useful information about registered IP rights can be gathered from public sources, in particular the relevant national IP offices. The registers will have information about the owners, the scope and status of the IP and any registered interests (e.g. securities for loans). But there is some information which a register search is unlikely to be able to provide. For example, whether a trade mark has been “used” within the last 5 years. (Failure to use a mark opens it up to challenge by a third party for invalidity.) Likewise, it is more difficult to conduct an investigation of unregistered rights from public sources, because there is no register to review, though some useful information may still be gathered with a bit of imagination – e.g. a seller’s unregistered brands may be reviewed by looking on their website or sales brochures. A buyer will, therefore, need to ask the seller questions about their IP. This is usually done by way of a formal or informal due diligence questionnaire. A seller may also disclose relevant documents.

In some cases, depending on factors such as the value of the transaction, such as the perceived risk and the buyer’s attitude to risk, the investigation may also include specific freedom to operate analysis on key commercial products, processes or trade marks used by the seller. This may involve, for example, searches for registered rights in the names of known competitors or more broadly across technology fields. Searches may also be conducted in some cases with a view to assessing the validity of the IP rights. (These documents are often known as “patentability opinions” or “freedom to operate (FTO) opinions”).

The due diligence questionnaire

A due diligence questionnaire is basically a series of questions about the seller’s IP estate. The buyer will expect the seller to answer these questions fully or to direct the buyer toward relevant documents in the seller’s data room which the buyer can review. Download a summary example questionnaire.

The report

These days due diligence reports tend to be “exceptions only”. Few people want to trudge through mere recitations of documents. They want to identify and focus on value and the key risks to the business, in particular, any issues around entitlement, infringement, freedom to operate, validity and the scope of the IP rights. Sometimes, in particular with patent estates, the report may focus a fair bit on the technical merits of the patents.

Material issues will need to be flagged and recommended actions proposed. After reading the report you should be able to make an informed decision on appropriate remedial actions, the allocation of risk, the price and even whether to proceed with the deal (though that is far less common than most people imagine).

The transaction

Once the due diligence process is concluded or, more likely, is underway, the transaction document will be drawn up, whether that is a sale & purchase agreement, an investment agreement, a licence etc.

From a due diligence perspective, the heart of all the transaction documents is the drafting and negotiation of the warranties and indemnities. A buyer will expect certain warranties to be given by the seller with respect to their IP. The warranties tend to track the due diligence questionnaire. Thus they will include a warranty as to title, whether the IP is valid and in force, that the seller has the right to dispose of the property, the existence of third party rights under the IP, that the rights are not being infringed, and that there is no one threatening infringement.

It is reasonable to caveat (or “qualify”) certain warranties “so far as you are aware”. It is impossible, for example, to be absolutely certain that there is no infringement risk with respect to IP, because it is impossible to conduct a complete search of databases around the world, or with any unregistered IP rights. Likewise, it is impossible to fully determine whether certain IP rights are valid (such as patents), since a third party may disclose documents of which the seller is unaware but which could impact on validity.

Sometimes a seller will decide to give warranties that their IP is provided “as is”. That is, (except with respect to title) that the buyer takes the IP as it is/uses it at their own risk. Universities often like this approach. But it is likely to result in the buyer “chipping the price” to reflect their additional risk.

A seller should be very careful about giving warranties which they do not fully understand or which are not suitably qualified. A seller must also disclose to the other side any risks or facts that cut across their warranties. Conducting an IP audit before the disposal process will help inform the seller at this stage.

The interplay between warranties and disclosure letters

Sometimes a seller will disclose particular or material facts with respect to their IP which will caveat their warranties in the transaction agreement. They may make such disclosures in a “disclosure letter” and/or a disclosure in their data room. To take an example: if the buyer asks a question about whether there is anyone infringing the IP, the seller may give a “clean” warranty that says that, so far as the seller is aware, there are no such infringements.

But in the disclosure letter the seller then caveats that warranty by reference to a disclosure in the data room of a known infringement.

Something to watch out for in a disclosure letter is a presumptive disclosure, in respect of registered IP, against publically available information. For example, wording along the lines of “all publically available information is deemed to be disclosed against the warranties”. This is usually unreasonable, because one cannot have complete awareness of what is contained in all public databases.

The interplay between warranties and indemnities

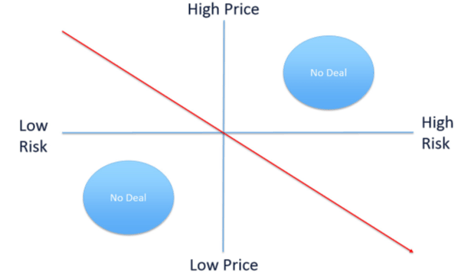

There may be circumstances where the buyer will seek an IP indemnity from the seller, for example against third party infringement claims arising from use of the IP that has been acquired. Whether an indemnity is reasonable depends on the type of deal on the table and the allocation of the risk between the buyer and the seller. The price of the IP is a matrix of that risk and benefit. If the IP is a strong and the seller is standing behind it and provides an indemnity, then the price will tend to be higher. On the other hand if the IP is provided “as is” with no indemnity and with the buyer having to enforce or defend the rights themselves, then the price will tend to be lower.

Figure 2: A graph describing the price of IP rights as a function of their risk. ©Mewburn Ellis 2016

There is no right or wrong way, or a “standard” approach, to IP, value or indemnities. It depends on the circumstances in question and the nature of the transaction. But you cannot negotiate price, warranties or indemnities from an informed position, either as the buyer or the seller, unless you have done your due diligence.

Post-transaction

Post-transaction actions will have been identified in the due diligence report or in the transaction document itself (perhaps as a contingent requirements). For example, filing an application to register an unregistered trade mark or invention. Sometimes it is necessary to record changes of ownership or names, licences or security interests. Doing so is fairly straight forward in the UK. But in other jurisdictions it can be more expensive, especially if there are necessary legalisation or their formalities. Often there are time limits. A buyer should, therefore, ensure that such post-transaction matters are organised and dealt with in a timely manner. There should also be a proper costing of the record all costs alongside the estimate for due diligence and the transactional work. This will avoid any unpleasant surprises after the transaction has completed.

Sean is a European IP lawyer. He is head of our legal services team and a member of our Management Board. He has over 20 years of experience advising on contentious and non-contentious IP matters, including patents, trade marks, designs, copyright, database rights and trade secrets. He has a particular focus on the life science, bioinformatics, pharma and advanced materials sectors. Sean works closely with senior management and their external advisors to deliver a wide range of IP related projects in a pragmatic and commercially-focussed manner, including on IP protection, commercialisation, technology transfer and litigation.

Email: sean.jauss@mewburn.com

Sign up to our newsletter: Forward - news, insights and features

Our people

Our IP specialists work at all stage of the IP life cycle and provide strategic advice about patent, trade mark and registered designs, as well as any IP-related disputes and legal and commercial requirements.

Our peopleContact Us

We have an easily-accessible office in central London, as well as a number of regional offices throughout the UK and an office in Munich, Germany. We’d love to hear from you, so please get in touch.

Get in touch