In Forward magazine edition 2, we met up with Team Bath Racing Electric (TBRe) who are driving the future of autonomous vehicles.

Walking home from school through the streets of Barcelona, Eduard Gascon and his grandfather would pause outside car dealerships and admire the slumbering beasts inside. Once he was old enough, Gascon's idea of a thrill became a 500-mile drive across Europe. He eventually moved to the UK to study mechanical and automotive engineering, choosing the University of Bath partly because of its Formula Student team - Team Bath Racing Electric (TBRe), which designs and builds racing cars. But ask Gascon, 22, what he now spends his days doing and his answer may surprise you: he's yanking drivers out of the race and helping to build the autonomous vehicles (AVs) of the future.

There's no consensus on when this future will arrive, nor on how exactly it will change our world (we only know it will). But, if the process of releasing self-driving cars onto busy streets were akin to launching a new pharmaceutical drug, then we are deep into clinical trials.

Cars created by Waymo, which began as Google's selfdriving car project a decade ago, have clocked more than ten million miles on public roads. In April, Uber announced that it has received nearly £1bn worth of new investment to develop AVs. The following month, General Motors revealed that it has raised another £1bn for its AV unit, already valued at close to £20bn. With this much investment, innovation is sure to follow, along with new patents and regulations to govern discoveries.

Left to right: Hang Zhou, Eduard Gascon, UV Wijesinghe, and Iñigo Monreal

For now, however, AV trials are mostly being done in controlled environments (throwing in a few surprises to confuse algorithms) or with a human hand hovering nearby, ready to take back control. The promise of self-driving cars often outpaces reality, says The New York Times, and there are many serious concerns obstructing the road towards full autonomy, particularly around safety, cybersecurity, ethics and liability. But, as Deloitte's 2019 Global Automotive Consumer Study found, changing stubborn consumer behaviour towards shared mobility (A Vs are expected to arrive first in the form of taxi or ride-hailing fleets) may hinge on young people who 'have fully embraced the precepts of a digitally enhanced existence'.

Global competition

That's where the Formula Student competition fits in. It's a global event that began in the US over 20 years ago. Different countries host their own versions of the educational competition, designed to give students practical, real-world experience. Teams manage themselves, write business plans, secure funding, research and produce designs and, often, build their own cars. It's a simulator that helps young people change gears from academia to the workplace.

In the UK, Formula Student is hosted by the Institution of Mechanical Engineers (IMechE).

'It's a unique opportunity to showcase nine months of hard work as a team,' explains Formula Student project leader Lucy Killington. 'There's always a great buzz. It's exciting and inspiring.'

More than 130 university teams from some 20 countries are competing this year. The grand finale will play out in Silverstone, north-west of London. For the first time, an AV/artificial intelligence (AI) category has been added to the line-up. The IMechE believes this will help the competition remain relevant.

Gascon and about 20 members of TBRe, with Mewburn Ellis as one of its sponsors, have their sights set on winning this new category. It's a big ask and they are the only team daring to bring their own vehicle - the other five will use AI -ready platforms provided by the IMechE, which allow them to focus mostly on the software needed to make the car autonomous.

AV essentials

At the most basic level, AVs must do three things: perceive, predict and act. To see, most use a combination of cameras, GPS, radar and 'lidar' (radar's expensive cousin, which uses pulses of light to map its environment). Prediction requires clever algorithms and powerful computers that identify objects and mimic, or surpass, the way human brains process information. Deciding how to act is fairly easy on a race track (ie, turn left, turn right, speed up or slow down), but incredibly difficult in the real world, where, for example, a car will have to decide whether to kill its driver to avoid causing multiple deaths. These questions will be confronted, but for now there are less philosophical challenges to overcome.

'You can teach the algorithm what traffic cones look like,' says Gascon. 'But if you taught it on a sunny day and now it's raining and there are reflections, it will get confused. Humans are very good at adapting to different environments, but computers, in principle, are quite dumb. If you put them somewhere they have never been before, you're never quite sure how they are going to react.'

Things like snow, plastic bags or tractor trailers can throw off an otherwise superhuman computer, and a lot of research is pouring in to feed the algorithms with data that enables better machine learning.

Although Gascon and his team don't have the funds to use the kind of technology Uber and Waymo use - things like lidar or computers that crunch hundreds of trillions of operations a second - they see themselves as pioneers, laying the foundation for future TBRe teams. 'We are building the next generation of AV engineers,' adds Gascon.

As project manager, his role is to get everyone working together. That includes mechanical and electrical engineers, computer scientists and even marketing students. To get a sense of it, think about the rivalries on the television show The Big Bang Theory, especially between Sheldon Cooper, a theoretical physicist, and Howard Wolowitz, an aerospace engineer. Engineers like to pull things apart and find quick solutions, Gascon explains, while computer scientists take their time to perfect a piece of code. Finding the balance between rushing and delaying a project is key.

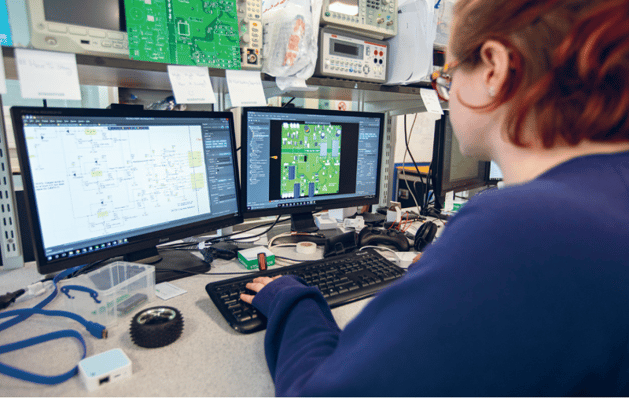

TBRe team's laboratory brings together a diverse collection of academic disciplines, degree structures and cultures

There are other dynamics too. Gascon is from Spain; the man in charge of the driverless car's motion, Hang Zhou, is from China; and the technical manager, Uvindu 'UV' Wijesinghe, was born in Sri Lanka and grew up in Botswana. There are TBRe members from Greece, Ireland and the UK. It's a diverse collection of academic disciplines, degree structures and cultures. The laboratory where it all comes together, on the eastern side of the sprawling Bath campus, kind of feels like an episode of The Big Bang Theory - super-smart people wrestling with super-complex questions. There's humour in the rivalry, not a whiff of desperation to win, and a genuine desire to explore.

Making the machine

On the hardware side, the driverless team has inherited last year's electric race car, which is being pulled apart and retrofitted to become autonomous. Turning the steering wheel and pushing pedals is being outsourced to robotic contraptions. On the software side, various open -source algorithms are being pulled together to give the car its brain. It will need to be able to accelerate in a straight line, go around curves and keep track of laps. Most importantly, it will have to understand where it is, its surroundings and how it can manoeuvre itself around obstacles. It will need to do some machine learning, one of Al's most murky corners. The competition rules state that cars have to go in blind, figure out their environment and then perform.

The TBRe car carried the university to victory last year, but back then it had a driver inside, and getting it track-ready for a new category requires plenty of work. At 250kg it's far too heavy. It needs a new battery and a lot of general maintenance. That's before the team even starts to install cameras, GPS equipment and computers. Frustratingly, a lot of the information gathered about the vehicle was lost when those who worked on it last year graduated.

This is something Gascon and the team plan not to repeat; they're keeping detailed notes.

The driverless project team must do what engineers do best: pull things apart, tinker and find solutions. Somewhere between the laboratory where the 'software skeleton' is being fused and a shipping container where the car is being modified lurks the potential for discovery.

'It's very exciting,' says Gascon. 'It makes you proud and it's so rewarding to see beyond these walls [of the university]. In the end, what's better than showing the world you can do something real?'

Silverstone awaits

With their academic programmes wrapped up, many TBRe members can now focus exclusively on the Formula Student project. Some, like Gascon, already have jobs to progress to.

Once he graduates, Gascon will move countries again, this time to work in Geneva and Germany, but staying in the automotive world. He believes technology is moving faster than legislation and there is a lot of work to be done in the legal and intellectual property sectors. As with car-making, the legal world, he feels, is colliding with tech and philosophy.

He hopes to see collaborations forming to help lawmakers and lawyers better understand how algorithms work and the logic behind a machine's action. Better knowledge in this field will help deal with issues of liability and accountability, he says.

'We need the legal profession to look at how companies develop cars and how they factor in the human aspects,' Gascon explains. To illustrate his point, he asks me to imagine crossing a road with an AV approaching. When there is no driver to interact with, how do I know that the car has seen me? What visual cues need to be designed? There have already been fatal accidents involving AVs in test conditions.

Ultimately, it is all these unanswered questions that draw Gascon towards AVs and their future. Does he want to keep driving? Sure. But he also believes that cars and computers should serve us and, if a self-driving vehicle will ferry him to work, save him time finding parking and ease city congestion, then, he says, I’m all for it'.

The findings of the Deloitte survey back this up. The majority of 25,000 respondents across 20 countries said they wanted AVs to save them time and keep them safe. Along with the safety aspect, there's a chance to reduce harmful emissions due to the close link between autonomous and electric cars. Like everyone else, Gascon has no firm answer for when A Vs will rule the roads. In the meantime, there's the Formula Student competition to prepare for: 'Bring on Silverstone!'

We caught up with TBRe after Silverstone to discuss their performance. Read about how they got on.

Simon is a Partner and Patent Attorney at Mewburn Ellis. He is highly skilled in patent drafting, prosecution, oppositions and appeals. Simon is also experienced in Freedom to Operate opinions. He is particularly interested in the invention capture process, marine engineering, and automotive engineering, especially automotive safety. He leads the firm’s sponsorship of UK electric Formula Student team, Team Bath Racing Electric.

Email: simon.parry@mewburn.com

Sign up to our newsletter: Forward - news, insights and features

Our people

Our IP specialists work at all stage of the IP life cycle and provide strategic advice about patent, trade mark and registered designs, as well as any IP-related disputes and legal and commercial requirements.

Our peopleContact Us

We have an easily-accessible office in central London, as well as a number of regional offices throughout the UK and an office in Munich, Germany. We’d love to hear from you, so please get in touch.

Get in touch.png?width=100&height=100&name=Simon%20Parry%20circle%20(4).png)