General Court (GC) in Case T-105/19 confirms EUIPO Board of Appeal (BoA) is not precluded from relying on ‘well-known facts’ in invalidity proceedings, as long as those facts substantiate the arguments and evidence of the applicant for invalidity. Furthermore, the GC ruled the BoA failed to carry out an overall assessment of the evidence of acquired distinctive character by limiting itself to an assessment of certain evidence in isolation.

Background

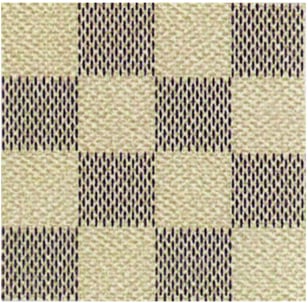

In 2008, Louis Vuitton Malletier (LV) obtained registration of the following figurative mark in the EU in respect of various fashion accessories in class 18.

LV's famous chequerboard pattern

An application for a declaration of invalidity was brought by an individual based in Poland, Mr Wisniewski, in 2015 on the grounds that the mark, comprising LV’s famous chequerboard pattern, lacked distinctive character. By a decision of 2016, the Cancellation Division upheld the invalidity action.

Appealing the Cancellation Division’s decision, LV requested annulment of the ruling. The BoA dismissed the appeal in Case R 274/2017-2 (“the contested decision”).

LV argued before the GC:

- The BoA incorrectly assessed the inherent distinctive character of the mark by relying on allegedly ‘well-known facts’, which is contrary to the rules concerning the burden of proof in invalidity proceedings; and

- The BoA erred in its assessment of acquired distinctive character by failing to conduct an overall assessment of the evidence.

‘Well-known facts’

In the contested decision, the BoA noted the mark consisted of a pattern and, as such, represented the outward appearance of the goods. Hence, the BoA relied on the test for distinctiveness applicable to three-dimensional shapes, which is that only marks which depart significantly from the norms and customs of the sector concerned are capable of guaranteeing to consumers the commercial origin of the goods. The BoA held the chequerboard pattern was commonplace in the decorative arts sector and that any notable variation from this standard print is absent from the mark. LV counter argued the BoA was wrong to factor allegedly well-known facts into its assessment because EU trade marks enjoy a presumption of validity, therefore the burden of proof lies with the applicant for a declaration of invalidity to file arguments and evidence calling the distinctiveness of the mark into question.

The GC noted that well-known facts are defined as ‘likely to be known by anyone or may be learnt from generally accessible sources’ and the BoA is entitled to rely on such facts in invalidity proceedings where they substantiate the applicant’s evidence. This is because the first instance examiner may have omitted consideration of these facts at the time the mark was first examined at application. The GC went on to confirm the BoA made no error of judgment by considering that it was a well-known fact that the chequerboard pattern was a basic and commonplace design that did not depart significantly from the norms of the sector. The GC therefore ruled the BoA’s assessment of the inherent distinctive character of the mark was sound and agreed with the BoA’s conclusions.

Incorrect assessment of evidence of acquired distinctive character

When carrying out the assessment of evidence, the BoA divided the EU Member States into three groups and limited its analysis to certain evidence specifically concerning the Member States of ‘group 3’ because LV did not have a physical retail presence in those territories. The BoA concluded the evidence relating to Member States in group 3 failed to meet the evidentiary hurdle for acquired distinctive character, which is to demonstrate that, through use of the mark, a significant part of the relevant public identifies the goods as originating from the owner. LV provided 68 exhibits in total, which included sales figures, invoices, advertising campaigns, press coverage, references and photos on social media, statements from independent organisations and public surveys. LV alleged the BoA, by excluding pieces of evidence, failed to assess the evidence as a whole.

The GC ruled the BoA erred in its assessment by choosing to examine only a small part of the evidence. This is because evidence of acquired distinctive character can relate to individual Member States, several Member States grouped together, or to the European Union as a whole. As such, the BoA was required to carry out a global assessment of all the relevant evidence submitted.

Furthermore, the GC emphasised that the absence of physical shops does not necessarily prevent the public from being exposed to, and recognising the mark, as originating from the owner. The GC referred to LV’s evidence of use online and on social media, including electronic catalogues and posts of the goods used by world-famous or locally recognised influencers, in addition to shops elsewhere in the most central and most popular tourist areas of major cities and airports, making the point that these sources are generally accessible throughout the EU. The GC therefore annulled the contested decision and the case will be reverted to the BoA for a decision on acquired distinctive character to be made afresh.

Take away points

This decision confirms the high legal hurdle to be met to demonstrate acquired distinctive character throughout the EU. Although the GC did not decide on the question of whether LV had met the necessary requirements, the clarification that the absence of a physical retail presence does not preclude the mark from having acquired trade mark significance, is a welcome one. It will be interesting to see how the BoA analyses LV’s evidence in light of this guidance.

The challenge faced by brand owners to maintain registration of non-traditional trade marks is ongoing. This category of marks is particularly vulnerable to post-registration issues due to the legal hurdles involved with demonstrating the marks are valid.

This blog was originally written by Pollyanna Savva.

Karolina is a trade mark attorney and a member of our trade mark team. Karolina's special interest include contentious proceedings, involving trade mark, copyright and design matters. She graduated with LLM in Intellectual Property Law and LLB Law with Another Legal System (Singapore) degrees from University College London. This included a year placement at the National University of Singapore, where she studied Singaporean law.

Sign up to our newsletter: Forward - news, insights and features

Our people

Our IP specialists work at all stage of the IP life cycle and provide strategic advice about patent, trade mark and registered designs, as well as any IP-related disputes and legal and commercial requirements.

Our peopleContact Us

We have an easily-accessible office in central London, as well as a number of regional offices throughout the UK and an office in Munich, Germany. We’d love to hear from you, so please get in touch.

Get in touch