Compelling advancements in cellular science could soon see us choosing to abandon animal agriculture. Forward explores the emerging world of cultured meat.

Forward: features are independent pieces written for Mewburn Ellis discussing and celebrating the best of innovation and exploration from the scientific and entrepreneurial worlds.

In August 2013, nutritional scientist Hanni Rützler and food writer Josh Schonwald sat down before the world’s media, picked up some gleaming cutlery and tucked into a burger worth €250,000. As the price tag suggests, this press junket with a twist was a watershed moment – because the snack in question was the first patty ever to have been grown in a lab rather than reared on a pasture.

The brainchild of researchers led by Maastricht University’s Professor Mark Post, the burger was the product of stem-cell technology, with Post’s team isolating muscle-tissue cells and growing strips of bovine flesh in conditions entirely removed from traditional farming.

Explaining the rationale behind his project, Post said: ‘Most people just don’t realise that current meat production is at its maximum and is not going to supply sufficient meat for the growing demand in the next 40 years. So we need to come up with an alternative… and this can be an ethical and environmentally friendly way to produce meat.’

Culture change

While the fanfare over Post’s burger eventually settled down, progress in the field broadly known as ‘cellular agriculture’ – the discipline of using stem cells to reproduce in lab settings vegetable matter or animal materials previously obtainable only from grown plants or farmed creatures – has not. The branch of this discipline for which Post’s burger blazed a trail is now commonly referred to as ‘cultured meat’.

One individual keeping a close eye on this arena is historian Benjamin Aldes Wurgaft, who last year published his book Meat Planet: Artificial flesh and the future of food. He tells Forward: ‘Cultured meat emerges out of two histories: one of tissue culture experiments, and one of thinking about the future of food, which stretches back to Thomas Malthus’s 1798 treatise Essay on the Principle of Population. It also benefits from a particular moment in early 21st-century elite culture: the belief – evident at TED conferences and the like – that virtuous philanthropy can solve major problems.’

‘In terms of promise and potential, there’s definitely a sense that what we’re seeing in this industry is analogous to the early days of the Big Tech brands,’ says Alex Shirazi, co-organiser of the annual Cultured Meat Symposium and host of the Cultured Meat and Future Food podcast. ‘You can see this clearly with the non-cultured meat, “Food 2.0” company Impossible Foods. It raised money as a tech company, branded itself as a tech company and scaled like a tech company.

‘Now is the time when innovation will flourish: I believe there will be more than $1bn invested in cellular agriculture over the next two years. We will also start to see the emergence of standards, many of which will be dictated by the food and safety watchdogs of each jurisdiction. In five to ten years’ time, all the major meat players will not only have active investments in cultured meat, but R&D teams exploring issues around scale and mass manufacturing.

Breaking with tradition

Already actively investing in the cultured meat sector is Agronomics. Formally launched in mid-2019, this ‘thematic investment’ firm evolved out of the business activities of renowned trend spotter, entrepreneur and philanthropist Jim Mellon. His partner in the venture, investor Anthony Chow, tells us that while the sector of cultured meat is ‘really quite nascent’, it has the potential to address major socio-political challenges that will only intensify in the coming decades.

‘The demand on our natural resources from animal husbandry is hugely significant,’ he says, ‘and with the world’s population predicted to reach 10 billion by 2050, we’re clearly on a trajectory that will create needs we cannot fulfil. Estimates vary, but between 15% and 20% of all greenhouse gas emissions come from animal husbandry, more than from all forms of transport combined. Around 50% of the fresh water we source goes into animal husbandry, including what we use to hydrate the crops we feed to farm animals, which in turn are highly inefficient machines at converting feed to edible calorie weight’

With the urgent need to reduce the carbon footprint of our food-supply chain, shepherd our natural resources and face up to the likelihood of future food scarcity becoming more evident every day, it’s clear that cellular agriculture could have a large part to play.

Dangerous proximity

But what of the actual eating experience? Could lab-grown meat yield its own branch of the ‘uncanny valley’ – that nagging not-quite-realness that blights our reception of CGI humans in films and games?

Chow concedes that public acceptance is ‘something to work on’ but thinks it will come, particularly from another angle. ‘The slaughter process is not just morally and ethically questionable,’ he says, ‘it’s just plain dirty. So the idea of growing meat in a sterile environment is going to be pretty helpful for boosting adoption. And what this year has highlighted, sadly, are the dangerous effects of exploiting animals for their meat, leather and other products.’

He stresses that our close interaction with animals, and placing them in cramped quarters in industrial farms, ‘increases the risk of future pandemics’. Up to 75% of new pathogens are known to emerge from zoonotic diseases.

To make a dent in public opinion, capital is key. Mellon’s empire made its first cultured meat investment in August 2018. ‘By that stage,’ Chow estimates, ‘there had probably been less than $100m invested in the sector. That’s peanuts compared with the $7.3 trillion value of the meat and seafood industry that lab production is seeking to disrupt.’

In parallel, though, the price point of the emerging sector’s outputs has dropped well south of the bill for Post’s experimental burger. ‘The Maastricht team’s commercial spinout claims it can now make a burger for about $10,’ Chow explains. ‘That’s still 20 to 30 times more expensive than it needs to be for mass-market adoption. But it shows that the process has become more efficient.’

With all that in mind, Agronomics is carefully nurturing an investment portfolio of firms that it hopes will, in next few years, help cultured meat come to fruition as a go-to consumer product. Forward spoke to three of them to find out how they hope to create a breakthrough that will make animal-free eating an everyday occurrence.

New Age Meats: The deli do-over

Founded in June 2018, New Age Meats has dedicated itself to perfecting a cultured version of that beloved deli classic, the pork sausage.

By the time he formed the company, New Age Meats CEO Brian Spears had chalked up 12 years of experience in the field of industrial automation, including eight managing his own business. As such, when New Age dawned, Spears imbued the firm with an ‘engineering-centric’ approach based around fine-tuning a production process to meet a clearly defined end goal.

By the time he formed the company, New Age Meats CEO Brian Spears had chalked up 12 years of experience in the field of industrial automation, including eight managing his own business. As such, when New Age dawned, Spears imbued the firm with an ‘engineering-centric’ approach based around fine-tuning a production process to meet a clearly defined end goal.

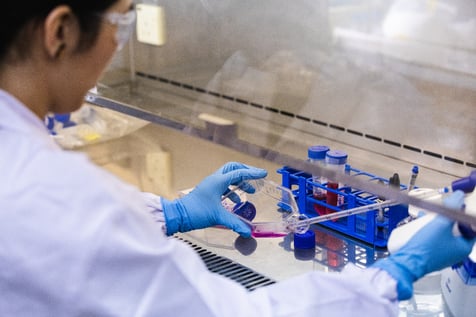

To make one of its sausages, New Age first biopsies a pig to obtain stem cells, then places the cells into a nutrient-rich ‘culture media’ that stirs the cells into mitosis. The nutritional environment is then tweaked to encourage cell differentiation between muscle, fat and connective tissues. Once there is enough cellular material, it is harvested, blended with spices and encased in non-animal-derived sausage skin.

Why specialise in that particular product? Spears explains: ‘Pork is physiologically similar to human tissue, so there was already a mountain of data out there on pork cells. That meant we didn’t need to spend investors’ money on doing fundamental research.’

"There was already a mountain of data out there on pork cells. That meant we didn’t need to spend investors’ money on doing fundamental research”

This enabled the firm to move quickly to prototype. ‘We went to biotech accelerator IndieBio in July 2018,’ Spears says, ‘and they provided us with seed funding the same month. The week the finance came in, we biopsied a pig, and two months later we held a tasting for 40 people in a downtown San Francisco brewery. Business Insider showed up and wrote about the sausage. They said it was smoky, savoury and tasted like breakfast. That left us with two big challenges: dropping the cost of the ingredients and scaling up production.’

There are regulatory hurdles to surmount too, for example in the form of USDA and FDA approval, plus compliance with the EU’s far stricter novel-foods rules. But Spears thinks that the New Age sausage will be on the market in ‘a few years’.

When it comes to IP in his market, Spears says that New Age has protected its innovations in ‘a variety of ways’, but he doesn’t consider the current patent landscape around cultured meat particularly competitive. ‘There are some very broad patents out there that, one, are about to expire and, two, wouldn’t stand up to scrutiny if challenged. So we’re not too worried about that.’

Shiok Meats: Creating cultured crustaceans

Scientist and entrepreneur Sandhya Sriram co-founded Singapore-based Shiok Meats in August 2018 with biotechnologist Ka Yi Ling. Both women have PhDs in stem-cell and developmental biology and come armed with more than 20 years of combined, relevant experience. With their arsenal of knowledge, they turned their attention to cultivating crustaceans – primarily shrimp, but also crabs and lobster.

Scientist and entrepreneur Sandhya Sriram co-founded Singapore-based Shiok Meats in August 2018 with biotechnologist Ka Yi Ling. Both women have PhDs in stem-cell and developmental biology and come armed with more than 20 years of combined, relevant experience. With their arsenal of knowledge, they turned their attention to cultivating crustaceans – primarily shrimp, but also crabs and lobster.

In part, that focus was a commercial decision: 65% of the world’s population lives in the company’s Asia-Pacific target market, and the region accounts for half of the crustacean sector’s annual $50bn value. But that strategic choice is underpinned by a far stronger moral conviction, born of Sriram’s first-hand experience of visiting some of the world’s largest shrimp farms.

Shiok Meats' cell-grown "shrimp" dumplings

‘Shrimp are bottom feeders,’ she explains. ‘In the ocean, they feed on dead animals and deep-sea plants. But the [traditional] seafood industry exploits that preference by growing them in sewage water. As a result, they come out black – so they’re cleaned in industrial bleach, dunked in huge vats of antibiotics and then sent off for human consumption. It’s absolutely appalling. I’m a vegetarian by choice and have never eaten shrimp. After seeing that, I can’t understand why anyone else would either.’

“Thanks to pollution, wild-caught shrimp are loaded with microplastics and heavy metals”

If you think that means Sriram has any greater respect for sourcing shrimp from their natural habitat, think again. ‘Thanks to pollution, wild-caught shrimp are loaded with microplastics and heavy metals,’ she notes. ‘And remember the gallons of bleach and antibiotics that are used to clean up sewage-farmed shrimp? They are dumped in the ocean. Plus, shrimp are caught in massive trawler nets with an alarming 1:20 ratio of by-catch [unintentionally caught animals] to shrimp. So countless other sea animals and plants are killed unnecessarily.’

Shiok grows its crustacean meat in a chamber called a bioreactor – not dissimilar to a brewery tank – in which specimens’ stem cells are suspended in a nutrient-rich liquid with carefully controlled temperature and pressure conditions, supported by gas exchange.

Shiok Meats focus on cultivating crustaceans

Sriram adds: ‘The entire technology of cell-based crustaceans is patented by us. We are currently in R&D and intend to commercialise in the next two to three years. Our long-term plan is to have multiple plants in various Asian countries, producing cultured crustaceans for their local markets, thereby reducing the products’ carbon footprint. We hope to sell in a majority of regional restaurants initially and are also looking into B2C/retail in the future.’

Bond Pet Foods: Better for your best friend

“My background isn’t in biotechnology, tech or veterinary nutrition,’ admits Rich Kelleman, CEO of Bond Pet Foods, ‘so I have no business being in the alternative-meats space!’

However, his journey towards founding Bond, which is based in Boulder, Colorado, is no less compelling than his previous career: in part, driving consumer awareness of meat products.

However, his journey towards founding Bond, which is based in Boulder, Colorado, is no less compelling than his previous career: in part, driving consumer awareness of meat products.

‘I spent 25 years in advertising,’ Kelleman explains, ‘and the account that brought me to Boulder ten years ago was Burger King. They wanted to understand how to compete with new brands such as Chipotle and Panera Bread, which were redefining what high-quality ingredients meant in the fast-food space.’

As a business and communications strategist, Kelleman researched Burger King’s business model in intimate detail and was immediately struck by the onerous challenges around procuring ingredients, particularly meat. While working on the account, Kelleman went vegan (‘That led to some interesting conversations,’ he says), and a few years later, he and his wife adopted their first dog.

Prototype pet food

The concerns he’d nurtured around meat procurement for burgers soon shifted to the field of pet food. He explains: ‘Looking at all the deep-rooted issues around farm-animal welfare, sustainability and safety, I started to ask: could there be a better way?’

“Looking at all the deep-rooted issues around farm-animal welfare, sustainability and safety, I started to ask: could there be a better way?”

Kelleman immersed himself in research around novel food solutions and quickly found out about companies such as Memphis Meats, Perfect Day Foods and Clara, which were looking to make steak, chicken, milk and eggs through biotech processes. As they were young startups, their CEOs and CTOs were happy to take calls. After picking their brains, Kelleman realised that if he were to make cultured meat for the consumption of pets rather than humans, the path to commercialisation would be relatively quicker.

Ecological factors, though, provided his greatest motivation. ‘In 2017,’ he explains, ‘a UCLA study found that US dogs and cats have an environmental toll equivalent to a year’s worth of driving 13.6 million cars. They’re responsible for 25% to 30% of the environmental impact of US meat consumption. If America’s dogs and cats were a country in their own right, their intake of meat would rank fifth in the world.’

Bond Pet Foods' laboratory in Boulder, Colorado

Bond’s process focuses on producing chicken muscle proteins, which it grows in bioreactors with yeast – a traditional pet-food ingredient – helping those cells to express the required proteins. The resulting material is then harvested, gently dried and used in a variety of cooking applications (for example, extruded into kibble, baked into a treat or topper). Kelleman is currently looking at a three-year timeline to regulatory approval and supermarket shelves.

Fast-moving market

Of course, the companies we’ve spoken to represent just a snapshot of an exciting sector. Alex Shirazi says the Cultured Meat Symposium is currently clocking in at about 70 companies, and believes that by the end of 2020 the sector will exceed 100 firms.

And for all of them, development will take time. ‘For cultured meat: the science is still in early R&D and just starting to move up to larger, pilot scale for manufacturing and growth, so it may be another decade before cell-cultured meat products are regularly available.

‘But while we don’t quite know when cultured meat will be ready, we do know that it is moving fast.’

Inflection point is coming

Adam Gregory, a partner in the life sciences team at Mewburn Ellis comments:

"For me, the thing that makes the cellular agriculture movement so exciting is its potential to contribute meaningfully towards addressing the challenges we face as a growing population – from the environmental crisis to global threats to public health – and in an ethical manner. As the cost of production continues to fall, I think we’re fast-approaching the inflection point where industry and consumers will no longer be able to justify production by traditional agricultural practices, with cellular agriculture being viewed as the only morally-responsible source of animal food products."

Find further thoughts from Mewburn Ellis on cultured meat here and the kinds of patent claims we might begin to see here.

Written by Matt Packer.

Images provided by New Age Meats, Shiok Meats and Bond Pet Foods.

Feature illustration provided by Michal Bednarski.

Adam is a Partner and Patent Attorney at Mewburn Ellis. He works with biotech companies to build and manage their patent portfolios, drafting patent applications and co-ordinating prosecution worldwide. Adam has particular experience handling portfolios relating to therapeutics (particularly immunotherapies, including adoptive cellular therapies), antibody technology, diagnostics, and regenerative medicine.

Email: adam.gregory@mewburn.com

Sign up to our newsletter: Forward - news, insights and features

Our people

Our IP specialists work at all stage of the IP life cycle and provide strategic advice about patent, trade mark and registered designs, as well as any IP-related disputes and legal and commercial requirements.

Our peopleContact Us

We have an easily-accessible office in central London, as well as a number of regional offices throughout the UK and an office in Munich, Germany. We’d love to hear from you, so please get in touch.

Get in touch