A recent decision of the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) has seen another trade mark registration for a famous Banksy artwork be cancelled on the grounds of bad faith. This comes quickly after a similar decision issued in September last year to cancel a trade mark registration for Banksy’s ‘Flower Thrower’ (see our blog Banksy’s ‘Flower Thrower’ trade mark cancelled for bad faith).

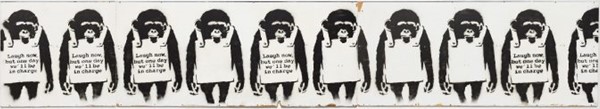

The recent decision concerns what the EUIPO described as “arguably the most famous and iconic” of Banksy’s artworks, ‘Laugh Now But One Day We’ll Be In Charge’ (better known simply as ‘Laugh Now’), which depicts a line of 10 monkeys wearing signs around their necks, some which include the above title and some which are blank.

Banksy's ‘Laugh Now But One Day We’ll Be In Charge’ artwork

Background

In November 2018, Pest Control Office Limited, Banksy’s legal handling entity, applied to register a part of the ‘Laugh Now’ artwork as a figurative European Union trade mark (EUTM) covering a wide range of goods and services in classes 9, 16, 25, 28 and 41, including sunglasses, posters, bags, building materials, textiles, clothing, rugs, games, toys, art exhibitions and commissioned artist’s services. No oppositions were received by third parties and the mark was registered in June 2019.

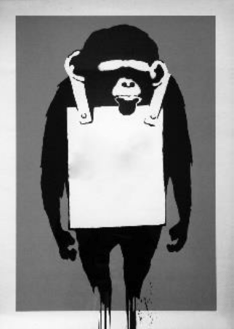

EUTM 17981629

Subsequently, in November 2019, Full Colour Black Limited (the same company who successfully invalidated the Flower Thrower registration) applied to invalidate the EUTM alleging, inter alia, bad faith.

The arguments

Full Colour Black argued that the sole purpose of registering the artwork as an EUTM was to prevent the ongoing use of the work which Banksy had already permitted to be reproduced. They noted that Banksy has previously permitted parties to disseminate their work and even provided high-resolution versions of the work on their website and invited the public to download them and produce their own items. On this point, they once again recited passages from Banksy’s book ‘Wall and Piece’ in which they stated that “copyright is for losers” and that that the public is morally and legally free to reproduce, amend and otherwise use any copyright works forced upon them by third parties.

Moreover, they alleged that Banksy does not legitimately use the registered mark as a trade mark. Rather, they said that the contested registration forms “part of a series of filings which constitute an attempt to monopolise images on an indefinite basis contrary to provisions of copyright law”, and the mark was only registered so that Banksy did not need to rely on copyright law for enforcement, which would require them to lose their anonymity. In this regard, they also argued that Banksy, via their representatives, has publicly expressed that the registered mark was not intended to be used and has concocted sham efforts to try and mislead the EUIPO into believing that there was such an intent.

The trade mark owner responded by contesting Full Colour Black’s evidence, claiming that it was insufficient to prove that the EUTM was filed in bad faith. They disputed the claim that Banksy had given “free reign” to the general public to use their copyright. Moreover, they argued that granting free reign for non-commercial use should not have any bearing on a trade mark in relation to commercial goods.

Further, just as they did in the Flower Thrower dispute, the trade mark owner relied on the Sky v SkyKick decision of the CJEU to demonstrate that “a party that registers a trade mark in pursuit of a legitimate objective to prevent another party from taking advantage by copying the sign is not acting in bad faith”. They said that Full Colour Black are taking advantage of the fact that Banksy cannot enforce any unregistered trade mark rights and/or copyright without losing their anonymity and damaging their public persona or business interests. They further argued that there is a legitimate objective in obtaining a trade mark registration through an incorporated company, meaning that the application was not made in bad faith.

The law on bad faith

Under EU trade mark law, an EUTM registration is liable to be invalidated where the applicant was acting in bad faith at the time of filing the application. There is no precise legal definition of the term ‘bad faith’ but, generally speaking, bad faith is likely to be established when the conduct of the applicant departs from accepted principles of ethical behaviour or honest commercial and business practices. This is decided by taking into account all the factors relevant to the particular case, and the burden of proof lies with the invalidity applicant who is alleging bad faith.

Bad faith may be established where it is apparent that the trade mark proprietor filed its application without any intention engage fairly in competition, or to use the registered trade mark in relation to the goods and services covered by the registration, but instead intended to undermine the interests of third parties, or to obtain an exclusive right for purposes other than those falling within the accepted functions of a trade mark.

The EUIPO decision

In its decision, dated 18 May 2021, the EUIPO considered the evidence and arguments filed by both parties in detail.

The EUIPO noted that Banksy had previously made clear statements that the public were free to download and use the artworks as they wished. Despite stating this should not be for commercial purposes, the evidence suggested Banksy was aware of various companies using ‘Laugh Now’ to commercialise goods and did nothing to stop them.

Moreover, they also noted that there was no evidence to suggest that Banksy was actually producing, selling or providing any goods or services under the contested sign prior to the date of filing of the contested EUTM. Subsequently, in October 2019 (a few months before the filing of the present application for invalidity) there was evidence that a Banksy shop was opened. This was not open to the public, but the public could look at the window displays and buy the products online, after a vetting procedure to ensure that they were not going to re-sell the items and were not art dealers. However, both Banksy and their legal representative had made clear statements that this shop was only opened to circumvent the non-use requirements under EU law. In particular, Banksy said that “the motivation behind the venture was “possibly the least poetic reason to ever make some art” – a trademark dispute” and “for the past few months I’ve been making stuff for the sole purpose of fulfilling trademark categories under EU law”. As such, the use made of the mark was not genuine use in order to create or maintain a share of the market by commercialising goods, and so could not be taken into account.

Overall, the EUIPO decided that the contested EUTM was filed in order for Banksy to have legal rights over the ‘Laugh Now’ artwork as they could not rely on copyright without losing their anonymity. This is not a recognised function of a trade mark, and so the EUIPO held that a filing of a trade mark cannot be used to uphold these rights.

Moreover, they considered that Banksy did not have any intention to use the EUTM in relation to the goods and services covered by the EUTM at the time the application was filed. The use which was subsequently made of the sign was made with the sole purpose of overcoming EU laws regarding the issue of non-use.

For those reasons, the EUIPO considered that the trade mark proprietor’s actions were inconsistent with honest practices as it had no intention to use the EUTM as a trade mark according to its function, and thus the EUTM was filed in bad faith. Therefore, the EUTM registration was invalidated in its entirety.

Comment

Following the recent cancellation of Banksy’s ‘Flower Thrower’ registration, the decision in these proceedings does not come as much of a surprise. The EUIPO has again taken a generous approach to the interpretation of bad faith and is unwilling to allow Banksy to enjoy the benefit of a trade mark registration simply to overcome the evidential requirements of a copyright infringement claim which would require Banksy to lose their anonymity. Looking ahead, this recent decision may signal the end of Banksy’s trade mark portfolio. Cancellation proceedings have been issued against 5 more of Banksy’s artworks which have been registered as EUTMs, and it seems likely that a similar decision will be reached in those proceedings.

Joe is an associate and a member of our trade mark team. He has an LLB Law degree from the University of Manchester and LLM in Professional Legal Practice from the University of Law, which encompassed the Legal Practice Course. At both undergraduate and postgraduate level, Joe completed modules on Intellectual Property law, which focussed on trade mark law and practice. Joe previously worked in the Business Crime and Regulation department at a solicitors’ firm on a high-profile criminal case.

Email: joe.mcalary@mewburn.com

Sign up to our newsletter: Forward - news, insights and features

Our people

Our IP specialists work at all stage of the IP life cycle and provide strategic advice about patent, trade mark and registered designs, as well as any IP-related disputes and legal and commercial requirements.

Our peopleContact Us

We have an easily-accessible office in central London, as well as a number of regional offices throughout the UK and an office in Munich, Germany. We’d love to hear from you, so please get in touch.

Get in touch