There are many different types of names you might see associated with a pharmaceutical product.

Each will have a chemical name or scientific name, which will depend on the particular chemical formula, and will typically be too long and complicated to be used to refer to the product on a day to day basis.

Companies developing a new pharmaceutical will therefore usually devise a generic name, or non-proprietary name, which is simpler and can be used by medical practitioners and their patients to more easily understand what the pharmaceutical in question is and does. The World Health Organization (WHO) co-ordinates the international non-proprietary name (INN) system. Each INN approved by WHO is globally recognised and open to use by all. Some countries also have their own naming systems.

At the same time, most companies will also want to create their own trade mark or brand name in order to distinguish their products from those being sold by other traders. Brand loyalty, particularly within the pharmaceutical sector, can ensure that a pharmaceutical company will still enjoy a significant market share even after any patent rights in the product have expired.

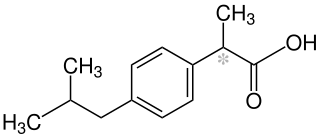

In order to illustrate the difference between generic names and trade marks, we can consider a type of over-the-counter (OTC) pharmaceutical most of us always have in our medicine cabinets at home: ibuprofen. The IUPAC (chemical name) for this painkiller is "(RS)-2-(4-(2-methylpropyl)phenyl)propanoic acid", whilst “ibuprofen” is the widely recognised INN / generic name. Ibuprofen is sold under a wide variety of trade marks or brand names across the world, including NUROFEN, ANADIN and CALPROFEN in the UK.

Chemical formula for ibuprofen

We will now look at some specific issues you should consider when choosing, clearing and registering a new pharmaceutical trade mark, focusing on the UK, but touching on issues with wider application.

Selecting a Trade Mark

When embarking on naming a new pharmaceutical product, it’s important not to ‘put all your eggs in one basket’ or narrow your choices too soon. Finding a name which is available for use and registration and which also meets with regulatory approval can be a long process and the searching, trade mark registration and marketing authorisation stages may all knock out possible options. It is therefore advisable to devise quite a long list of possible names and gradually narrow the options down until you find a name which meets all the criteria required.

Typically the strongest types of trade marks consist of invented words or words which have no meaning in the context of the product or any of its characteristics. However, from a marketing perspective, many pharmaceutical companies prefer names which in some way reflect the therapeutic area or part of the body that the medicine will be used in. If that is the case, care should be taken to ensure that the names are still distinctive and memorable enough to function as a badge of origin, otherwise they could confuse or mislead consumers, and are likely to be refused registration.

It is also a good idea to avoid names that are too closely linked with the generic name of the product, although it is common for pharmaceutical companies to choose a brand name that is reminiscent of the generic name to an extent, as in the examples of NUROFEN and CALPROFEN discussed above, both of which share the suffix “ROFEN” with ibuprofen.

Trade Mark Searching

Prior to adopting a new trade mark, it is important to conduct trade mark searches to check if that mark is likely to be available for use and registration. This is particularly the case with pharmaceutical trade marks where confusion on the marketplace could have extremely serious consequences.

When embarking on a searching project for a pharmaceutical product, there will usually be a large number of trade marks being considered. Therefore, it can be helpful to start with some identical trade mark searches on an international basis. Identical searches can help to identify if there are likely to be any very serious obstacles to use and registration in a particular jurisdiction, for example an identical mark already registered in class 5. It may help to ‘knock out’ some of the possible trade marks on your list prior to incurring the higher costs involved in comprehensive searching.

Once you have conducted any identical trade mark searches, you should move onto conducting full trade mark clearance searches in the countries of interest. The key here is to search as widely and broadly as your budget will allow, so that potential problems can be identified prior to significant further investment of time and resources.

In addition to searching the relevant trade mark registers, you should ensure searches for pharmaceutical trade marks cover INNs and any other relevant country specific generic names. You may also want to include some ‘pharma in use’ searching, where checks are made of relevant databases of pharmaceutical names that are actually in use.

It is also a good idea to incorporate local advice on the meaning of your chosen mark(s) in your searching to ensure that they do not convey a negative image in the key countries of interest.

Your trade mark attorney can help you devise an appropriate international searching strategy.

Trade Mark Registration

Once your trade mark searches have narrowed down your list of possible names, it is time to consider trade mark applications. Ideally you will want to try and keep your options open by applying for a few different names, perhaps three or four, in case there are any unexpected objections from the trade mark offices, a third party, or the relevant regulatory bodies.

Your trade mark attorney can assist with creating an international filing strategy, taking into account the jurisdictions of interest, costs, how quickly registration is required, and a number of other factors. If there are several different territories of interest, it is likely to be worth considering the Madrid Protocol system. The Madrid Protocol is an international system for obtaining trade mark protection for a number of countries and/or regions using a single application.

However, the timing of filing trade mark applications for pharmaceutical products can be a tricky issue to navigate. Obtaining marketing authorisation for a pharmaceutical product can take a very long time, but in most countries, a trade mark registration will become vulnerable to cancellation for non-use if the mark is not put to genuine use for the registered goods/services for a certain number of years after registration. The relevant period varies from country to country but is typically either 3 or 5 years (it is 5 years in the UK). In other countries, such as the US and the Philippines, it is also necessary to file evidence of use periodically simply to achieve and/or maintain registration.

The issue of whether you can rely on the fact that a pharmaceutical product is the subject of ongoing clinical trials, or awaiting regulatory approval, as evidence of use of a trade mark or as justification for non-use is a particularly difficult one.

In the EU, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) held in ‘BOSWELAN’ in 2019 that use of a mark in clinical trials does not constitute genuine use and that preparations for future marketing can qualify as genuine use, but only if entry to the market is imminent. The Court did not rule out the possibility that pending clinical trials could constitute a “proper reason” for non-use in some specific cases, but the time elapsed since registration, the duration of the trials, and whether the owner has taken any steps to speed up the regulatory approval process would all need to be considered.

In a more recent decision concerning an application to revoke the registered trade mark NOCDURNA for non-use, the EUIPO held that pending marketing authorisations for pharmaceutical products in the EU constitute a proper reason for non-use of an EU trade mark registration. This will be reassuring for owners of pharmaceutical trade marks in the EU. However, decisions on acceptable non-use will always turn on their own facts. Furthermore, a decision of the EUIPO Cancellation Division is not binding on the UKIPO or the UK courts.

It is therefore important to strike a balance between applying for UK trade marks as soon as possible in order to secure the earliest possible filing dates, and not acting so early that trade mark registrations become vulnerable to non-use cancellation before the mark is ever put to use in the UK. This is likely to involve waiting until you are reasonably sure that clinical trials will be concluded, and marketing authorisations achieved, within five years.

Regulatory Approval

Before they can be used, new trade marks for pharmaceutical products must also be approved by the appropriate body regulating medicines in the relevant country. In the UK this is the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA).

The MHRA reviews each application for a product name to ensure that the proposed name will allow the medicine to be taken safely and correctly. It will reject a proposed trade mark if it is liable to cause confusion with the name of any existing medicinal product, or if it is misleading with respect to the therapeutic effects, composition or safety of the product. Further information is available in the MHRA naming of medicines guidance.

It is important to note that the processes and assessments of the UKIPO and MHRA are distinct: the UKIPO will not check if a trade mark is approved for use in relation to the goods for which it is registered, whilst the MHRA does not consider a trade mark registration justification alone for accepting a proposed name.

Key Recommendations

- Keep your options open as long as possible by searching and registering a number of potential trade marks;

- Choose trade marks which are either invented words or words which have no direct connection with your product;

- Avoid trade marks that are too closely linked with the generic name or which could be considered misleading;

- Search as widely and broadly as your budget will allow;

- Consider starting with identical trade mark searches to identify any ‘killer’ problems;

- Follow up with comprehensive searches in key territories, including generic names, ‘pharma in use’ and advice on meanings/connotations;

- File trade mark applications when you are reasonably sure that clinical trials will be concluded and marketing authorisations achieved before any resulting trade mark registrations become vulnerable to non-use cancellation; and

- Remember a trade mark registration does not guarantee acceptance by the regulatory bodies.

Rebecca is a Partner and Chartered Trade Mark Attorney at Mewburn Ellis. She handles all aspects of trade mark work, with a particular focus on managing large trade mark portfolios, devising international filing and enforcement strategies, and negotiating settlements in trade mark disputes. Rebecca has extensive experience of trade mark opposition, revocation and invalidity proceedings before the UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO), including very complex evidence based cases. Rebecca also has a strong track record in overcoming objections raised to trade mark applications.

Email: rebecca.anderson@mewburn.com

Sign up to our newsletter: Forward - news, insights and features

Our people

Our IP specialists work at all stage of the IP life cycle and provide strategic advice about patent, trade mark and registered designs, as well as any IP-related disputes and legal and commercial requirements.

Our peopleContact Us

We have an easily-accessible office in central London, as well as a number of regional offices throughout the UK and an office in Munich, Germany. We’d love to hear from you, so please get in touch.

Get in touch