Elizabeth Maclennan developed a love of speed at Mewburn Ellis-sponsored Team Bath Racing Electric. Now she’s helping shatter records at McMurtry Automotive.

Forward: features are independent pieces written for Mewburn Ellis discussing and celebrating the best of innovation and exploration from the scientific and entrepreneurial worlds.

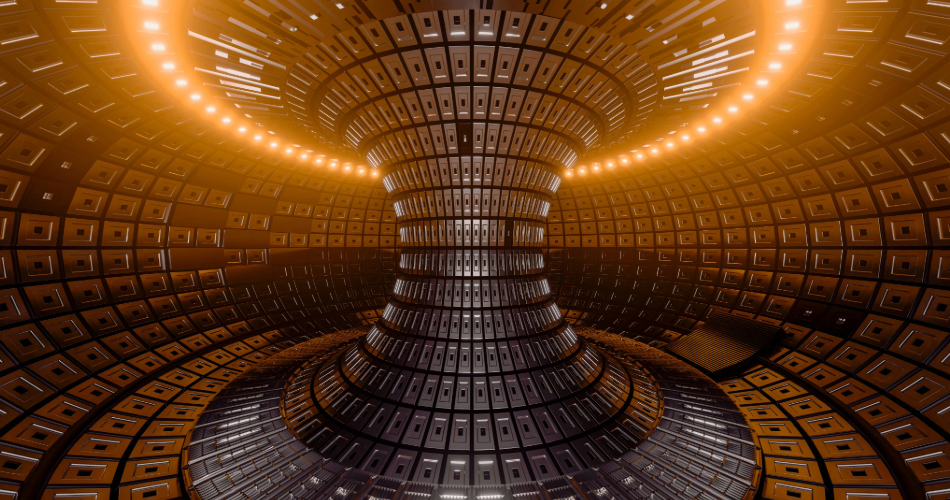

One glance and everyone wants to ask the same question: How fast does it go? The McMurtry Spéirling looks like the Batmobile, rippling in carbon fibre. So, does it live up to the hype?

“We’ve been testing at the Silverstone grand prix circuit with Max Chilton, who raced in Formula One,” reveals Elizabeth Maclennan, project manager at McMurtry Automotive. “On days that aren’t even our strongest we are already overtaking established combustion race cars.”

However you spin it, that’s eye-watering. The Spéirling is so fast that even Max Chilton is having to re-calculate some of his driving style. And it’s being upgraded. “We’ve got two tonnes of downforce, which is an absolutely monstrous amount,” says Maclennan. “We are still not in the marginal gains phase. We’ve put three or four years into it and we’re still making huge improvements to efficiency and performance using new materials.”

The head-to-head comparison isn’t entirely fair. The Formula One car would be handicapped by its petrol engine. The McMurtry Spéirling is 100% electric, so it’s able to deliver instant torque at will. And the newcomer has a hidden advantage. “We have a downforce on demand system which makes the car unique,” says Maclennan. “It’s a system where two large fans in the back of the car behind the driver’s head evacuate air from a sealed area underneath the car. That area of low pressure applies downforce to give really excellent grip on the tyres. You can fly around tracks.”

You won’t see this technology in F1. “Oh no, it’s totally banned. Gordon Murray [the legendary F1 car designer] was one of the first to try it. The Brabham BT 46 B ran for one race, in the Swedish Grand Prix, and it just destroyed all of its rivals. It was seconds ahead of everybody else. And then it got banned. Bernie Ecclestone realised this was not good for business.”

This is a startling vehicle, which was the intention from day one. The billionaire engineer Sir David McMurtry, who made his money with precision instruments company Renishaw, founded the company that bears his name to create something truly original. McMurtry Automotive is his baby – a well-funded enterprise to push the limits of what’s possible on four wheels.

“Our goal is to build the world’s fastest electric car,” says Maclennan. This model – the first out of the McMurtry research lab – is already a contender for the title. It’s too cutting edge to comply with F1’s race regulations, but you might catch a glimpse of it testing at an elite circuit.

An equally fascinating question is how Maclennan got here. At just 28 years old, she’s a core part of a team most engineers would kill to be a part of. Yet as a teenager, she confesses, she had no interest in cars.

Her tale is compulsory reading for anyone keen to promote talent. It includes how she overcame sexism, how she found her niche, and how she endured a lonely time as a woman in the industry. Her tale also highlights how small initiatives can make a huge difference to the career of young and talented professionals.

Elizabeth Maclennan posing with a previous version of the McMurtry Spéirling

Meet Team Bath

Maclennan’s first sniff of a racetrack came at Williams Advanced Engineering, the consultancy branch of the Williams F1 team. She had just completed two years of an engineering degree at the University of Bath and landed a place there on a one-year paid internship. Not a bad place to start out.

“Before then I wasn’t fussed about cars,” she says. “I did that internship and suddenly, thought ‘Oh yeah, cars are awesome.’” Williams felt the same way about her. “I think interns are quite popular because we’re really enthusiastic and cheap labour. There were three in my year. In the following year, Williams hired eight or ten people, so they thought we were worth having.”

She worked on designing wiring harnesses for batteries to go inside hybrid electric cars. “The work was for the batteries for all the Formula E teams. Later, I did some wiring work for the Jaguar Formula E team, which was very cool. Various cars, track cars, simulators – there was even work on a last-mile electric bike. It’s quite varied!”

On her return to the university, she put her new-found knowledge to practice. She enrolled in Team Bath Racing Electric, which each year enters Formula Student. The electric car series was in its second year. With Maclennan fresh from Williams, who better to steer the team to glory?

She ran the show. “They’d sometimes call me team lead, sometimes project manager, sometimes ma’am. And sometimes mum.” With a laugh, she says, “Mostly it was a sarcastic ‘Leave me alone mum’ or ‘Mum, stop making me fill in forms...’”

Maclennan’s natural charisma, combined with a steely administrative flair, helped the team expand to 25 students. It absorbed her life. “I worked on Formula Student like I had a full-time job,” she says. “I got in at eight every morning and I would leave at six, and that was the beginning of the year. When the competition was round the corner, we’d leave at 3am. The day before my graduation, I went to university at eight and left at four in the morning. Then I got up at seven to go and graduate.”

The team didn’t win the series, but it finished seriously high out of the 120 entrants. She treasures her memories of the experience. “The camaraderie is huge. If the team is working well, it’s incredible.”

She’s grateful to the sponsors who made it possible. Mewburn Ellis in particular played a major role in keeping the team afloat. Maclennan is vocal about the need for companies who want to promote talent to take action like this.

“Mewburn Ellis contributed a significant amount of money,” says Maclennan. “We also went to a number of events with them. Their support was really, really helpful. The opportunities students get through extra-curricular activities like this can be life changing.”

For Maclennan, it served as a stepping stone into her current job. The managing director of McMurtry each year arranges a presentation to the Team Bath Racing students, to convince them to apply for jobs. “They couldn’t tell us any details about the car because it was hyper confidential,” recalls Maclennan, “So I don’t know how they convinced us it was the best thing ever. But they did. Five or six of us applied for jobs there.”

Maclennan started in project management, but later expanded her role. She got the job of handling intellectual property – the company’s crown jewels. “I was trying to get my head around how we would begin to protect intellectual property. And that’s when I remembered Mewburn and the help they’d given us. We had a meeting in a café, and the rest is history.”

McMurtry currently has 15 patent applications in the works, with five approved. “We are very ambitious with our patenting strategy,” says Maclennan. “We’ve tried to patent the core tenets of the business. We are lucky that what we are doing is quite different from other car manufacturers. Our downforce on demand system is subject to quite a number of patents.”

The focus on IP comes from the founder, Sir David McMurtry. He worked at Rolls-Royce designing Concorde engines. He came up with an idea for a trigger probe – a sort of spring-loaded needle which detects the edges of objects in order to measure them. His story is a parable for Maclennan: “Rolls-Royce weren’t interested in commercialising it, but David thought, ‘No, this is the start of something’ and bought the patent from Rolls-Royce for not too much money. That’s how Renishaw began. Now it’s a multi-billion-pound global business. So David’s success is down to the fact that his ideas were patented from the start. He then defended them and built a reputation as an inventor who is not to be messed with.”

The McMurtry Spéirling is 100% electric, so it’s able to release instant torque.

A woman in engineering

A subject close to Maclennan’s heart is the experience of being a woman in her profession. She’s blunt about the challenges. “It’s lonely,” she says. “It was the same at university, at Formula Student, at Williams, and at McMurtry. There aren’t very many of us. Every now and again you realise that you’re the only one who has your lived experience. There’s an aspect of that that does sometimes get hard. Most of the time you don’t feel any different. But there are times when you do, and those are sad, because there’s not much you can do about it.”

Whilst McMurtry is an egalitarian workplace, this was not so at other places Maclennan has worked. “During my gap year, page three of The Sun would be handed around the break room. I was right there. That felt absolutely horrendous.” She takes a pause. “Obviously they didn’t get it. It makes me emotional now thinking about it, my 18-year-old self being in that vulnerable situation and feeling so unwelcome. There are probably workplaces that are still like that.”

She recommends that women in her profession find a circle of friends and allies to call on when needed. “Having a group of women that you don’t work with, but in a similar professional situation as you, is life-saving. I have friends from university, women I’ve met professionally, and others I’ve picked up along the way. These can be people who are earning different amounts or working in the public sector or wherever. Have a variety. I recently had a really interesting chat with a friend who does music therapy for the NHS, so a completely different field, and we just had so many similar experiences.”

Organisations can help men understand some of the errors they make. “I have mixed feelings when someone swears and then says sorry to me because I’m a woman. On the one hand, I appreciate people making the effort to be polite. On the other hand, I don’t want to be picked out as different.” Again, the men who do this are unaware how alienating this can be.

Investing in talent is the long-term remedy. Formula Student helped Maclennan find a career in cutting-edge automotive research. Companies that want to contribute to improving the prospects of students can fund similar projects.

Speaking in schools promotes that interest even earlier. When Maclennan was at school, she mentioned an interest in engineering. “It was an all-girls school. The teachers said, ‘Sorry? What?’” She’s taking a lead in addressing this. “I’m always getting emails from my old school to go back and talk about engineering,” says Maclennan. “Whenever I do, there is a lot of interest.”

There’s also the issue of role models. The adage that it’s hard to become what you can’t see resonates. Pioneers such as Claire Williams, who was deputy team principal at Williams F1, and Susie Wolff, current CEO of Formula E team Venturi, are leading the way. Maclennan is now a figure that others can look up to and emulate.

World-beating

For now, her focus is resolute. The goal is to perfect McMurtry’s first car and prove its performance with high speed records. The first being attempting victory at the Goodwood Festival of Speed (UPDATE 26 JUNE 2022: On 26 June 2022, The McMurtry Spéirling won the 2022 Goodwood Festival of Speed Hillclimb and also broke the all-time record – sensationally clocking in at 39.08 seconds! Read more).

McMurtry Automotive is a new brand in a competitive industry. But with a philanthropic billionaire behind it, and a philosophy of pursuing breakthrough technologies, there’s no limit to what it can achieve.

That said, who wouldn’t like to see that race with an F1 car? “It’s an interesting prospect. We generate our downforce in an entirely different way to an F1 car. An F1 car relies on its wings to generate downforce at high vehicle speeds, whereas our downforce is generated by onboard powered fans, giving instant downforce from 0mph. The net result is that the Spéirling delivers more downforce than an F1 car at speeds up to 150mph, and with significantly less drag. It’s interesting to consider this is all in a package with zero tailpipe emissions. We have some planned upgrades after the Festival of Speed too, so watch this space. Its too tough to call which vehicle would prevail."

On the front line of a motor racing revolution

Simon Parry, a Partner and Patent Attorney in the engineering team Mewburn Ellis, comments:

As a car nut and motorsports fan myself, I’ve found it particularly enjoyable to work with Elizabeth and her colleagues at McMurtry Automotive since the beginning of their ambitious Spéirling project, and to be involved with the downforce concept originally pioneered by the great Gordon Murray. It has been astonishing to follow the rapid development of their revolutionary car, and my colleague Dan Brodsky and I are very excited to follow McMurtry’s future plans as they take on the established players.

It has also been an absolute pleasure to witness Elizabeth's career develop from first meeting her through our sponsorship of the team at the University of Bath and to be touched by her infectious enthusiasm for the team and its engineering achievements.

Written by Charles Orton-Jones

Images provided by McMurtry

For more information about automotive visit our Automotive Spotlight page.

UPDATE 26 JUNE 2022: On Sunday 26 June, the McMurtry Spéirling, driven by Formula 1 driver Max Chilton, won the 2022 Goodwood Festival of Speed Hillclimb and also broke the all-time record – sensationally clocking in at 39.08 seconds! Read more.

Simon is a Partner and Patent Attorney at Mewburn Ellis. He is highly skilled in patent drafting, prosecution, oppositions and appeals. Simon is also experienced in Freedom to Operate opinions. He is particularly interested in the invention capture process, marine engineering, and automotive engineering, especially automotive safety. He leads the firm’s sponsorship of UK electric Formula Student team, Team Bath Racing Electric.

Email: simon.parry@mewburn.com

Sign up to our newsletter: Forward - news, insights and features

Our people

Our IP specialists work at all stage of the IP life cycle and provide strategic advice about patent, trade mark and registered designs, as well as any IP-related disputes and legal and commercial requirements.

Our peopleContact Us

We have an easily-accessible office in central London, as well as a number of regional offices throughout the UK and an office in Munich, Germany. We’d love to hear from you, so please get in touch.

Get in touch.png?width=100&height=100&name=Simon%20Parry%20circle%20(4).png)