We live in a world filled with patterns. The natural world reveals to us many patterned arrangements, from the veins on autumnal leaves, to the spirals which appear on the surface of seashells.

The arresting effect of patterns is as fierce on commercial goods, as it is in the natural world. Famous examples of this are the “Burberry check” which has been used to line Burberry raincoats since the 1920s, and Louis Vuitton’s fabric which incorporates the iconic ‘LV’ emblem. These examples show how patterns can act as brand identifiers, helping consumers to connect a product with its unique owner.

Here we explore registration of patterns as trade marks in the UK and consider how common challenges may be overcome by applicants.

Can I register a pattern as a trade mark?

A pattern mark differs from other categories of marks. It is a sign which consists executively of a set of regularly repeated elements. Often, applicants may use geometric shapes or designs repeatedly on the surface of their products to convey information about the brand owner.

Yet an interesting conundrum arises: the fact that patterns carry a common aesthetic appeal may present various legal difficulties during the trade mark application process.

Whilst it is entirely possible to register a pattern as a trade mark in the UK, obtaining a registration of any specific pattern may prove to be more challenging than it is for other categories of marks, such as word and logo marks. Hopeful applicants need to be aware of the some of the difficulties that need to be surmounted first.

What legal challenges may a pattern face in the trade mark application process?

One of the hurdles that must be overcome by a sign, in order to be registered as a trade mark, is the so-called ‘distinctiveness’ criteria. Distinctiveness is a legal term which simply means that a sign can serve as a guarantor of origin of the unique owner’s product or service. Whether a sign has distinctive character is assessed by asking whether it can be used by consumers as an indication of a single trade origin.

Pattern marks are a category of signs which are less likely prima facie to have distinctive character initially, but the distinctive character of each application will be examined based on the facts [1].

In many cases, consumers would consider a pattern as no more than a decoration on the product itself, or its packaging. Patterns that are commonplace, traditional and/or typical – such as floral designs, tartan or polka dots – would not be capable of guaranteeing the origin of the product to consumers.

On the other hand, if a pattern is unusual, departing from the norm of the relevant market sector, or is, more generally, capable of being easily memorised by the target consumers, it may meet the distinctiveness requirement.

Overall, the trade mark examiner will ask: Is the pattern unusual and memorable for the relevant public, purchasing the relevant products or services?

A polka dot pattern for clothes would most likely be refused registration as it is undeniably commonplace. Yet the same pattern may fare better in a trade mark application for toasters!

Connecting the dots…with a Birkenstock sandal

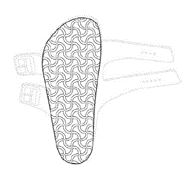

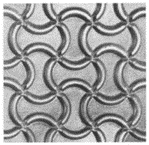

We can gather some useful insights about how to overcome the challenge of proving the distinctiveness of a pattern mark, by looking at the application to register the pattern on the sole of a sandal as a trade mark.

A well-known shoe company, Birkenstock, applied to register a sign “consist[ing] of a pattern applied to the sole of footwear (especially sandals, clogs and slippers)”, pictured below:

|

|

- Acquired distinctiveness

One way in which Birkenstock attempted to meet the distinctiveness requirement in the UK was by showing that the mark had gained distinctiveness through actual use in the market. It is open to applicants in the UK to give evidence that a sign has built a distinctive character because of how effectively it has been used in the market over a period of time. In other words, the applicant can argue that since their mark has been used so extensively, consumers have been educated to interpret the sign as an indication of its trade origin.

Based on Birkenstock’s evidence, the tribunal was not convinced that the sign had acquired distinctive character through use. However, as this assessment is done on an individual case basis, it is always open to applicants to provide their own evidence which just might meet the threshold.

- Categorisation of the mark

In the EU, Birkenstock tried another round of arguments. It argued that the assessment of whether a sign “depart[s] significantly from the norms of the sector” should not have been applied to its mark in the first place. It argued that the criterion that the sign should “depart significantly from the norms or customs of the sector” to be distinctive should not apply, as this stringent criterion applies exclusively to shape marks (also known as ‘3D’ marks) and not to other categories of marks [2].

The Court of Justice of the European Union (‘CJEU’) disagreed. It confirmed that if a mark can be interpreted as a surface pattern, then it can be assessed as a pattern – irrespective of its actual categorisation on the application form [3]. It also affirmed that the criteria of “significant departure” applies to pattern marks, equally as it does to shape marks [4].

The CJEU confirmed that a mark will be assessed in “light of the nature of the products at issue” to consider whether “the sign at issue may in fact be held to constitute a surface pattern” [5]. Only when the sign is unlikely to be used as a surface pattern, due to the nature of the products covered by the application, will it not be assessed as a surface pattern. In short, the CJEU confirmed that the relevant assessment involves looking at what the possible uses of the sign are [6].

As it was possible that the sign could be used as a surface pattern, the CJEU affirmed that the test of whether the sign presents a “significant departure” from the norms of the relevant sector, should have been applied in this case. In light of that criterion, the application for “footwear” products was denied, as the sign did not depart significantly from what consumers are accustomed to seeing on shoe soles.

Key takeaways from our Associate in the trade mark team: Becky Campbell

|

When choosing a pattern which you hope to register as a trade mark, some of the points you should consider are:

- Making the pattern more unusual from what is normally seen in the relevant sector;

- Whether you can bolster your chances of success by providing evidence that your pattern has become distinctive through actual use in the market, prior to the date of the application;

- Seeking advice as to whether to register your mark as a figurative, or pattern mark, or perhaps seek duplicate protection.

The process of obtaining a trade mark registration of a pattern may prove a little more mind-boggling than cross-stitching, but it can bring some undeniable benefits to your brand!

Look out for our next article on shapes as non-traditional trade marks to stay up to date with the most current developments.

References

- Starbucks (HK) Ltd v British Sky Broadcasting Group Plc [2012] EWHC 3074 (Ch); quoted in UKIPO decision O-505-16 (paragraph 55)

- Board of Appeal decision R 1952/2013-1 contested in Birkenstock Sales v EUIPO, C-26/17 P

- Birkenstock Sales v EUIPO, C-26/17 P, paragraph 36

- Birkenstock Sales v EUIPO, C-26/17 P, paragraph 34

- Birkenstock Sales v EUIPO, C-26/17 P, paragraph 39

- Birkenstock Sales v EUIPO, C-26/17 P, paragraph 40

Karolina is a trade mark attorney and a member of our trade mark team. Karolina's special interest include contentious proceedings, involving trade mark, copyright and design matters. She graduated with LLM in Intellectual Property Law and LLB Law with Another Legal System (Singapore) degrees from University College London. This included a year placement at the National University of Singapore, where she studied Singaporean law.

Sign up to our newsletter: Forward - news, insights and features

Our people

Our IP specialists work at all stage of the IP life cycle and provide strategic advice about patent, trade mark and registered designs, as well as any IP-related disputes and legal and commercial requirements.

Our peopleContact Us

We have an easily-accessible office in central London, as well as a number of regional offices throughout the UK and an office in Munich, Germany. We’d love to hear from you, so please get in touch.

Get in touch