Chemical inventions are subject to the same criteria as all inventions at the European Patent Office (EPO). Additionally, there is some case law and practice which is particularly relevant to chemical and pharmaceutical inventions. This practice is specific to the EPO. One such practice is the assessment of ‘selection inventions’ which is regularly needed for chemical and pharmaceutical inventions.

What are selection inventions?

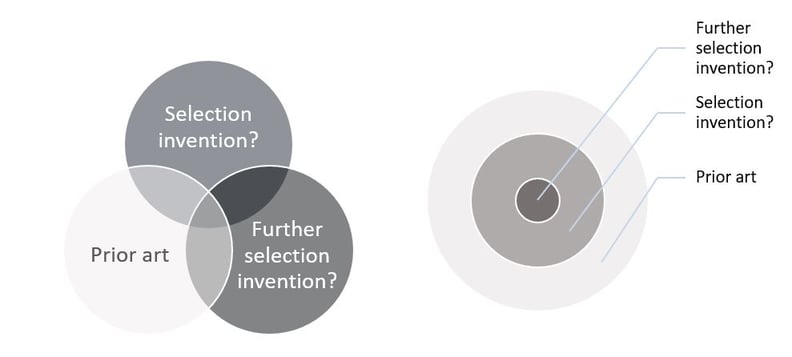

Selection inventions are inventions which fall within or overlap with disclosures in the prior art. It is possible for there to be more than one “selection invention” which falls within or overlaps with disclosures in the prior art.

At the EPO, the assessment of selection inventions is based on the general principle that prior art disclosing a genus does not take away the novelty of a species falling within this genus. For example, a prior art disclosure of “a metal” does not take away the novelty of a specific metal, such as “copper”.

At the EPO, selection inventions are divided into three types:

- selection from lists in the prior art;

- selection of a sub-range from within a broader range in the prior art; and

- selection of a range which overlaps with another range in the prior art.

When assessing the patentability of selection inventions, the normal criteria applied to all other inventions similarly applies.

Novelty is considered based on the prior art disclosure (T 666/89). If the prior art clearly and unambiguously discloses the subject matter of the selection, the invention lacks novelty in the normal way.

If the selection is not clearly disclosed in the prior art, EPO case law has established additional tests to assess novelty of the selection invention. These tests are different for the three different types of selection invention (outlined above). Each test will be explained below.

i) Selection from lists

Selection from lists refers to the case when the claimed invention is defined by some components that are mentioned in lists of possible components in the prior art.

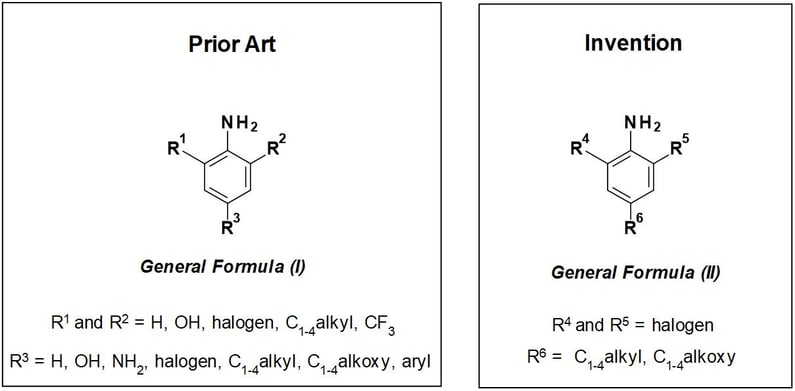

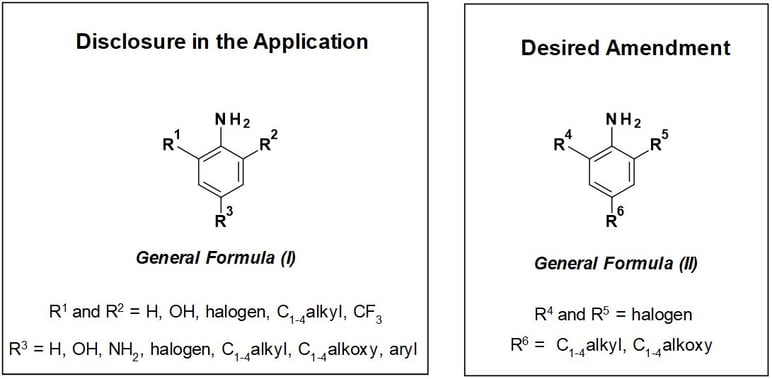

For example, consider the compounds shown below. The aniline compounds of the prior art are defined by general formula (I). In this general formula, each of the substituent groups at positions R1, R2 and R3 can be selected from a list of possible substituent groups.

The invention also relates to aniline compounds. The compounds of the invention are within the scope of general formula (I) in the prior art.

In the invention, the substituent groups at positions R4, R5 and R6 are selected from the list of substituent groups disclosed in the prior art.

Are the compounds of the invention novel at the EPO?

For selections from lists, the EPO applies a so-called “two list principle” (T 12/81). Here, the EPO specify that:

"if a selection from two or more lists of a certain length has to be made in order to arrive at a specific combination of features then the resulting combination of features, not specifically disclosed in the prior art, confers novelty” [EPO Guidelines G-VI 8].

Typically a list of “certain length” means the list must have at least three elements. However, if selections are being made from multiple lists (i.e. from more than 2 list) then a smaller list of two elements may be deemed to be of sufficient length (T 686/99).

A selection from a single list, no matter how long the original list or how short the selection, is generally not considered to be enough to confer novelty to a selection.

For the example aniline compounds, the invention represent a selection from 3 lists (i.e. R1, R2 and R3) that are each of “certain length” (i.e. containing 5 or more elements). Following the two-list approach, the compounds of the invention will therefore be considered novel over the prior art compounds of general formula (I).

The two-list approach also applies to other chemical and pharmaceutical inventions, such as mixtures, compositions, combination treatments and chemical processes.

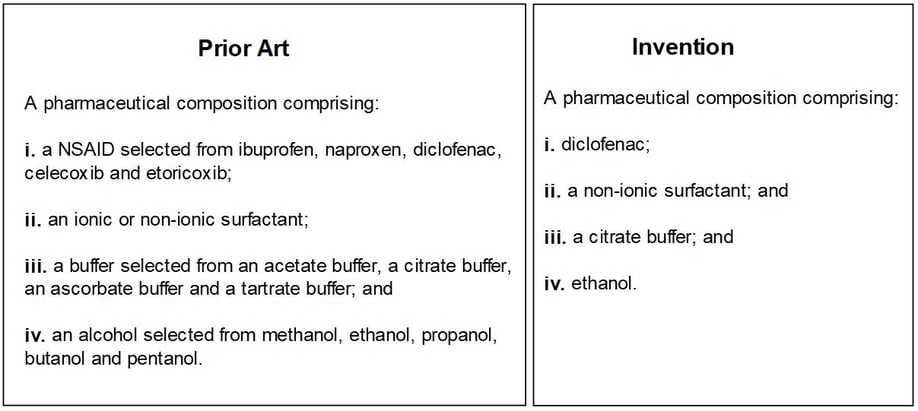

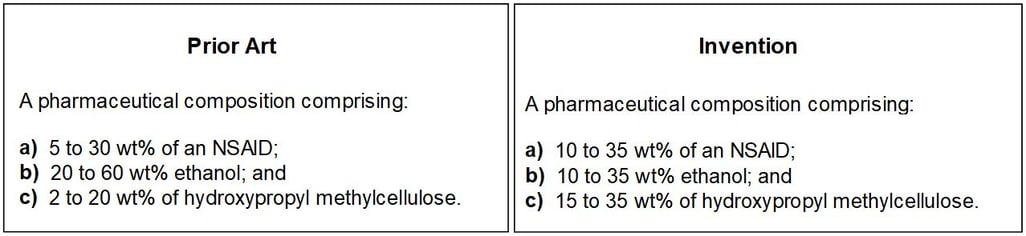

For example, consider the invention relating to a pharmaceutical composition in the following example:

Following the two-list approach, this invention will be considered novel over the prior art because each of components (i, iii and iv) is selected from a list of a certain length. Component ii is selected from a list of only two components in the prior art. In this case, this does not matter because the selection invention criteria are met by components i, iii and iv.

In summary, a general disclosure of a species defined by several lists of components (e.g. a chemical Markush claim) does not take away the novelty of an individual species (e.g. compounds). When preparing patent applications relating to inventions characterised by a selection from lists it is important to look closely at the prior art to assess what is novel before the EPO. Multiple fall-back positions relating to specific combinations of the novel features can then be included in the application to maximise the chances of success at the EPO. Multiple fall back positions are also important at the EPO for amendments due to the strict assessment of added subject matter (discussed in detail below).

ii) Sub-ranges

A sub-range refers to a claimed (narrower) range that falls within a broader range disclosed in the prior art.

Ranges of component amounts are often key to chemical inventions, and are frequently used to define chemical inventions in the fields of:

- compositions;

- alloys;

- liquid mixtures;

- polymers; and

- reagents in methods of synthesis.

EPO case law and practice regarding the assessment of novelty of sub-ranges changed in November 2019.

Previously, the key EPO cases for assessing novelty of sub ranges were T 198/84 and T 279/89. Prior to November 2019, it was necessary for three criteria to be met for a sub range to be considered novel:

- Narrow as compared to the known range;

- Far removed from specific examples and end-points of the known range; and

- Not arbitrary (“purposive selection”)

The recent practice change means that step 3 in this analysis is removed. That is, after 01 November 2019 it is no longer necessary for sub-range to be a purposive selection. This change applies to all pending applications irrespective of their filing date. Instead, this requirement is now assessed under inventive step.

Under the new law, a sub range now only needs to be narrow compared to the known range and far removed from specific examples and end-points of the known range.

This means it is much easier to establish novelty for an invention defined by a new sub-range. This is particularly relevant in situations where the prior art is ‘novelty only’ prior art under Article 54(3) EPC.

It is important to understand what the terms “narrow” and “far removed” mean. These terms are open to interpretation and are generally assessed on a case-by-case basis.

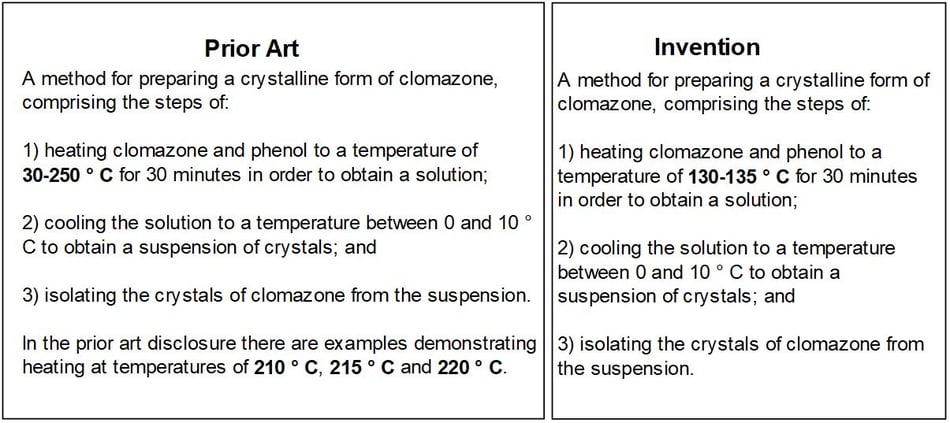

To demonstrate the assessment of “narrow” and “far removed”, it is helpful to consider the following example:

The prior art range covers 220°C. The range of the invention is only 5°C. At the EPO, the sub range of the invention is considered narrow.

The prior art end points are 30°C and 250°C. The claimed range is 100°C away from the nearest end point. Also, the prior art examples all exceed a temperature of 210°C. At the EPO, the sub-range of the invention is also considered far removed.

The invention would therefore be considered novel before the EPO.

Inventions characterised by sub-ranges can therefore be considered novel before the EPO.

When preparing patent applications relating to inventions characterised by sub-ranges, the important thing to consider is whether the claimed sub-range is “narrow” and “far removed” from the known range. When drafting an application, including fall-back positions that focus around the preferred sub-range is recommended. These fall back positions provide options for addressing any novelty objections whilst maintaining the broadest allowable claim scope at the EPO. Multiple fall back positions are also important at the EPO for amendments due to the strict assessment of added subject matter (discussed in detail below).

iii) Overlapping ranges

Of the three types of selection invention outlined above, overlapping ranges are the least common type.

Perhaps this is because the EPO considers the end points of ranges in the prior art as disclosures. This means a single range which overlaps with a known range is not considered novel. For example, an overlapping range of 50 to 70 is not novel over the prior art range of 1 to 52 because the EPO consider that 52 is disclosed.

Overlapping ranges are more commonly encountered in situations where there is overlap in the general scope of a claim, rather than overlap of one single feature (as is shown schematically in the figure below).

To help assess novelty of such overlapping ranges, the EPO has established a test of “serious contemplation”.

Here, the EPO Guidelines (G-VI 8) specify that:

“it must also be considered whether the skilled person, in the light of the technical facts and taking into account the general knowledge in the field to be expected from him, would seriously contemplate applying the technical teaching of the prior-art document in the range of overlap. If it can be fairly assumed that he would do so, it must be concluded that no novelty exists”.

For novelty of an overlapping range the assessment typically relies on establishing why the skilled person will not work in the overlapping region.

Again it is helpful to look at an example to demonstrate the type of assessment for overlapping ranges:

The invention overlaps with the prior art for all three components.

For novelty, the EPO will consider whether the skilled person will ‘seriously contemplate’ working in the area of overlap based on the prior art teaching. Typically, the default position for the EPO is “yes”; the skilled person will consider working in the area of overlap as this is disclosed in the art.

To establish novelty for an invention defined by an overlapping range, it is necessary to overthrow the EPO’s default position.

Generally, this can be achieved by looking at the examples and the specific disclosures in the application. For example, if all the examples are far away from the overlapping region, we can argue that the skilled person will not really seriously consider working in the area of overlap.

It is helpful (and often necessary) to look closely at the whole disclosure of the prior art when considering overlapping ranges. For example, are there any statements in the prior art which teach that the area of overlap should be avoided, or that this region is less preferred to other areas of the range? If so, the disclosure can be used to argue that the skilled person will not “seriously contemplate” working in the area of overlap.

EPO case law concerning the novelty of selection inventions characterised by overlapping ranges is open to interpretation and is assessed on a case-by-case basis. Thus, it might be helpful to consult your European Patent Attorney when preparing or prosecuting a patent application relating to overlapping ranges before the EPO.

Some general important practice points to consider are:

- Include a good description of the prior art in the introductory section of the application. This allows you to explain the invention by providing a clear description of what is taught/not taught in the prior art. This can be extremely helpful in demonstrating the novelty of the overlapping range;

- Include (many) fall-back positions. Fall back position are extremely useful for any future amendments to the claims that may be required to establish novelty. The EPO can be very strict about added subject matter so it is advisable to provide explicit fall back positions for both individual elements and the combination of individual elements. Such fall back positions allow maximum flexibility when making amendments to address an objection.

Inventive step

The normal inventive step considerations applied to all inventions before the EPO similarly apply to selection inventions. That is, the selection invention must be non-obvious in view of the prior art.

Here, the EPO Guidelines (G-VII 12) state that:

“If [the] selection is connected to a particular technical effect, and if no hints exist leading the skilled person to the selection, then an inventive step is accepted”

In practice, when assessing the inventiveness of selection inventions, the EPO often look for evidence (e.g. examples) that the selection claimed provides an effect that is not present outside the selected subject matter. This effect is often referred to as the “unexpected technical effect”.

Often the best way to demonstrate an “unexpected technical effect” is to show an effect by comparison with an example from the prior art or an example outside the selected subject matter (e.g. outside the claimed sub range).

Including comparative examples in a selection patent application can be very useful and is recommended for any patent application that is to be prosecuted before the EPO.

Of course, not all prior art is known at the time of drafting and perhaps not all experimental evidence is ready for the filing date. This is not a problem at the EPO. The EPO permit (and often encourage) submission of post filed data to support inventive step. So, we can later file data to demonstrate an unexpected effect at the EPO provided there is some indication in the application that the effect is provided by the invention.

What about amendments?

Another important point for consideration, which is related to novelty of selection inventions, is the basis for making amendments to the claims under EPO practice.

Consider, for example, a patent application containing two or more lists of certain length and an amendment which involves selecting only certain groups from these lists. Is this amendment allowable at the EPO?

The answer is most likely no. The concept of disclosure is generally considered to be unified. This means the ‘two-list’ approach for assessing novelty of a selection invention also applies for the assessment of amendments. Put another way, if a proposed amendment is ‘novel’ it is considered to contain added subject matter and is not allowable at the EPO.

For example, consider again the aniline compounds outlined above for selections from lists.

In this example, the compounds of general formula (I) now represent the disclosure in the application and the compounds of general formula (II) represent the compounds the applicant wants to claim.

The desired amendment will not be considered allowable before the EPO. The amendment requires selection from three lists (as discussed above). Said another way, the amendment requires many deletions of alternatives from several lists. In fact in this case, two of the lists have been amended to only a single possibility. The EPO will consider formula (II) to contain added subject matter.

However, not all amendments from multiple lists of alternatives are considered in the same way by the EPO.

For example, amendments based on multiple selections from converging lists of alternatives are generally considered allowable by the EPO (T1621/16). An example of a converging list of alternatives is “less than 10, preferably less than 8, more preferably less than 6, most preferably less than 4”. Such lists are generally considered to be different to non-converging lists of alternatives, such as “methyl, chloro, nitro and cyano”.

Another example is an amendment based on shrinking lists of alternatives, which are also generally deemed allowable before the EPO. Here, deletion from multiple lists is considered allowable as long as the shrinking of the generic group does not lead to “a particular combination of specific meanings of the respective residues which was not disclosed originally or, in other words, did not generate another invention” (T615/95). The allowability of such amendments is determined on a case-by-case basis and generally depends on the size of the original lists and the number of deletions being made. A few deletions from lists of “certain length” are generally considered allowable. However, shrinking lists through many deletions of alternatives from several list is generally not deemed allowable (as in the case of the example above).

Generally, in order for amendments from multiple lists to be considered allowable at the EPO, explicit basis from the application is required and is certainly advisable when drafting an application.

When preparing patent applications containing multiple lists for prosecution at the EPO, it is therefore important to consider whether any sub-lists (fall-back positions) detailing preferred and suitable combinations of features of particular interest may be required.

Strategic use of selection inventions

Selection inventions are often used as a strategy for securing additional patent term for compounds or compositions that are already broadly covered by another patent.

For example, consider again the aniline compounds outlined above. The applicant has a patent with claims to the compounds of general formula (I). The applicant later discovers that the compounds of general formula (II) have increased activity. The applicant can file a new “selection” patent application at the EPO directed towards the compounds of formula (II).

The compounds of formula (II) are covered by both the broad initial patent and the newly filed “selection” patent application. The patent term for the “selection” patent application runs from its filing date and expires later than the broad initial patent. This means the patent protection for the compounds of formula (II) is extended beyond the term of the broad initial patent.

Of course, selection inventions of this type are only possible if the initial application does not disclose the features of the later selection. When preparing applications for prosecution at the EPO, it is important to consider the relationship between fall-back positions in the earlier broad application and novelty of a later selection patent application.

For example, providing many fall back positions can be helpful to address any objections particularly in the case of unknown prior art. However, the fall back positions themselves are narrower (selected) disclosures.

A selection invention patent must be novel over the narrower fall back positions in the prior art not just the broadest disclosure.

The balance between fall back positions and potential future selection patent application depends on many factors. Some of these cannot be known at the time of filing the initial broad patent application. In some cases it might be helpful to consult your European Patent Attorney when considering such filing strategies.

Summary

Inventions which fall within or overlap with disclosures known in the prior art are generally considered allowable before the EPO.

The patentability of these selection inventions often depends on how closely related the selection is to the prior art disclosure, and whether a technical advantage is demonstrated by the selection.

When preparing “selection” patent applications for prosecution at the EPO it is important to ensure that the claimed selection can be defined in a manner that is novel over the prior art under the EPO’s practice discussed above. The inclusion of fall-back positions in the application is useful for providing options to address any objections and maintain the broadest possible claim scope.

Where available, comparative data that demonstrates an advantage over the prior art is highly recommended for a selection patent application. As discussed above, comparative data is often persuasive in demonstrating the inventiveness of a selection invention.

Finally, for an invention defined by lists of components or ranges, it is very helpful at the EPO to provide multiple fall-back positions in the application. These fall back positions should focus on preferred narrower combinations of the components or narrower ranges. Without explicit basis in the patent application, the EPO will often consider an amendment to contain added subject matter.

Overall, selection inventions before the EPO provide a useful means for protecting innovations in the field of chemistry.

This blog was originally published in the Japan Patent Attorneys Association (JPAA) Journal in December 2020 (Vol. 73, No. 14). View the original publication.

This blog can also be found in Korean here.

Eleanor is a Partner and Patent Attorney at Mewburn Ellis. She is also our Sustainability Champion and is responsible for leading the firm’s environmental strategy and our sustainability collaboration group, ensuring this remains an important focus for the firm. Eleanor is passionate about the role technology can play in a more sustainable future and enjoys working in close partnership to use her expertise to advance the commercial goals of her clients in this important area with a particular focus on sustainable chemical and material inventions.

Email: eleanor.maciver@mewburn.com

Sign up to our newsletter: Forward - news, insights and features

Our people

Our IP specialists work at all stage of the IP life cycle and provide strategic advice about patent, trade mark and registered designs, as well as any IP-related disputes and legal and commercial requirements.

Our peopleContact Us

We have an easily-accessible office in central London, as well as a number of regional offices throughout the UK and an office in Munich, Germany. We’d love to hear from you, so please get in touch.

Get in touch