A study of the consequences of filing third party observations (TPOs) in the MedTech sector and the interaction between TPOs and EPO oppositions.

You come across a patent application that will pose a problem for your business if granted. What do you do? Should you file third party observations? Or would it be best to wait to see whether the patent gets granted and then file an opposition? On the one hand, you might imagine that the more attempts you make at knocking out a patent, the better. However, on the other hand, you might be concerned that third party observations would amount to showing your hand too soon, leading to the grant of a patent that is more robust and potentially harder to knock out in a subsequent opposition.

Analysing EPO data from patent applications and granted patents for MedTech inventions, we sought guidance that might help answer the question of whether or not to file third party observations.

What are third party observations?

Many patent offices, including the EPO, UKIPO and DPMA provide a mechanism for third parties to file observations against a pending patent application. The desired result of doing this is generally to achieve a limitation or refusal of the application. In some jurisdictions, the practice is still relatively new, with both WIPO and the USPTO having introduced mechanisms for filing third party observations in 2012.

At the EPO, which is the main focus of this study, observations may be filed in relation to the grounds of: novelty and/or inventive step, clarity, sufficiency of disclosure, patentability and unallowable amendments. The ability to file observations in relation to clarity of the claims can be particularly useful, as this is not a ground of post-grant opposition.

Third party observations (TPOs) may be filed anonymously.

More information about TPOs can be found on our website article Third Party Observations explained.

Our Study

Using purpose-built scripts, we ran analysis on data collected from the EPO’s bulk data sets on MedTech patent applications filed over the past 10 years. The study covered data from patents and patent applications with IPC codes A61 (minus A61P) and A61Q.

We chose to focus on MedTech for this particular study because previous analysis of opposition rates across various engineering and ICT sectors had revealed that opposition rates were greater in MedTech as compared to other sectors (see our Special Report on EPO Opposition Trends in Engineering and Software).

Our Findings

The percentage of cases upon which TPOs are filed is low

Across the patent application and patents in the IPC codes we looked at, the rate of TPOs in the MedTech field was just 0.67%.

Of the applications upon which TPOs had been filed, there were some cases that had received multiple TPOs. Thus, although 1985 cases had just one TPO, 354 had two TPOs, 86 had three TPOs, 40 had four TPOs, and 13 had five TPOs.

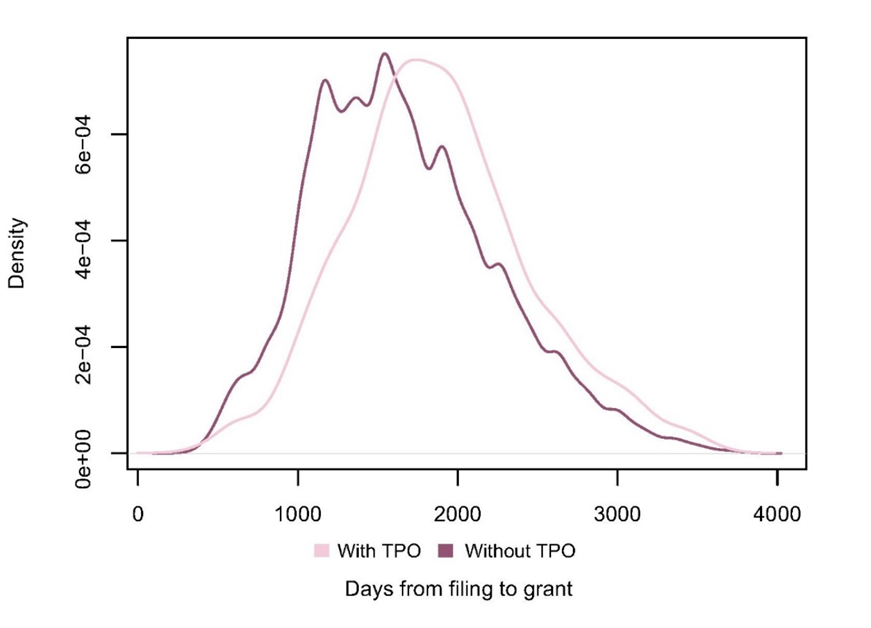

TPOs delay the grant of patents

The average time from filing to grant for patent applications without TPOs was 1668 days, while for patent applications with TPOs, the average was 1878 days. Therefore, the average grant time was delayed by 210 days for applications which had TPOs filed against them.

Fig. 1 - Density distribution of days from filing to grant for applications with and without TPOs

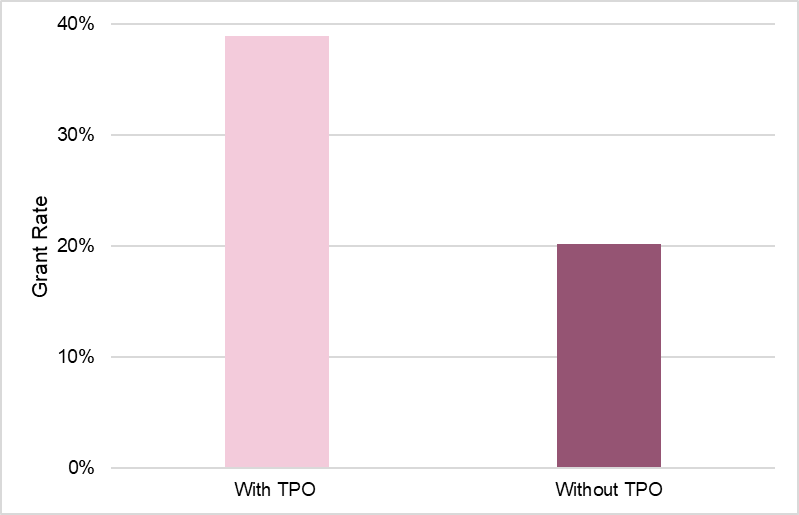

Filing a TPO does not make it more likely that the patent application will be refused

Of the patents and applications in our dataset upon which TPOs had been filed, 38.9% had been granted. Of the applications in our dataset without TPOs, 20.2% had been granted. In other words, applications with TPOs are at least as likely if not more likely to go to grant than applications without TPOs.

Fig. 2 – Grant rate for patent applications with and without TPOs

However, it would be wrong to jump to the conclusion that TPOs work against the third party by helping the patent proprietor to achieve grant. The higher grant rate of patents having TPOs could partly be a result of the TPO group being skewed towards applications that are further along in prosecution (third parties often wait to see how prosecution develops before filing TPOs). Additionally, the TPO group may be skewed towards applications upon which the EPO has already expressed a positive opinion.

Furthermore, our data does not enable us to determine whether or not a TPO resulted in restriction of the claim scope.

Regardless, the data certainly indicates that having TPOs filed against an application is by no means an indication that the application is less likely to proceed to grant.

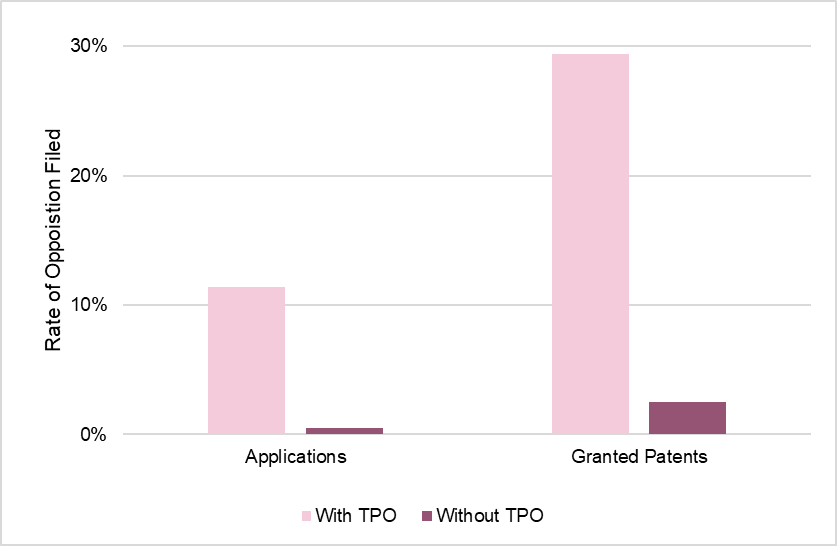

Patent applications upon which TPOs have been filed are more than ten times more likely to be opposed.

Of the 373,854 applications filed in our MedTech sample over the past 10 years, 0.59% have been opposed.

Breaking this down, 11.4% of applications with TPOs on their files were subsequently opposed, compared with the 0.51% of applications without TPOs.

Focusing only on the granted patents within our dataset (i.e. those capable of being opposed), 29.4% of granted patents with TPOs on the EPO register were subsequently opposed. This is in contrast with the 2.5% of granted patents without TPOs.

Fig. 3 – Rate of Oppositions filed against applications and patents with and without TPOs

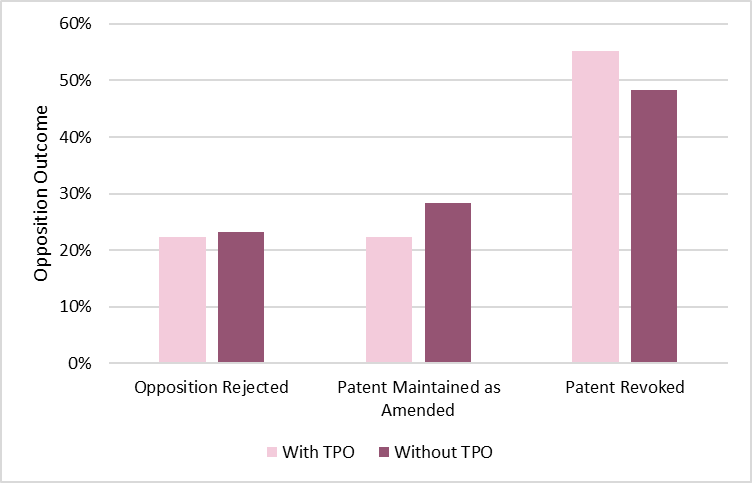

Filing a TPO against a patent application during prosecution does not significantly affect the chances of knocking it out in an opposition

For the decided oppositions in our dataset, we looked at the outcomes (i.e. whether the opposition was rejected, the patent was maintained as granted, or the patent was revoked). We found that regardless of whether or not TPOs had been filed against the patent during prosecution, the result of oppositions was similar.

Of the oppositions decided on cases with TPOs: 22.3% oppositions were rejected, 22.3% patents were maintained as amended, and 55.3% of the oppositions resulted in the patent being revoked. Of the oppositions decided on cases without TPOs: 23.3% oppositions were rejected, 28.3% patents were maintained as amended, and 48.3% of the oppositions resulted in the patent being revoked.

Fig. 4 – Opposition outcome for patents with and without TPOs

Even though patent applications that receive TPOs are much more likely to be opposed, the likelihood of a different possible outcomes of the opposition does not change significantly depending on whether TPOs had been filed during prosecution or not.

Take home messages

TPOs are a mechanism by which third parties can try to affect the prosecution of a “problem patent” in a cost-effective manner.

Importantly, our analysis shows that the risk of “showing your hand too early” by filing TPOs seems to be low. Filing a TPO against a patent application during prosecution did not significantly affect the chances of knocking it out in an opposition. Of course, there will always be exceptions to the rule; for example, “added matter” issues under Art 123(2) EPC may be fairly straightforward for an applicant to address during prosecution, but can lead to larger problems for a proprietor after grant because of the prohibition under Art 123(3) against extending scope of protection post-grant (the well-known Art 123(2)/123(3) trap). Accordingly, third parties may be advised to exclude “added matter” issues under Art 123(2) EPC from TPOs and reserve them instead for oppositions.

Perhaps surprisingly, our analysis revealed that applications with TPOs are at least as likely, if not more likely, to go to grant than applications without TPOs, although as explained above this could be due to applications with TPOs being unrepresentative of applications as a whole. Moreover, what our data cannot reveal is whether those applications with TPOs were granted with narrower claims than would have been the case if the TPOs had not been filed.

Ultimately, the decision about whether to file TPOs is one that should be taken on a case-by-case basis, weighing up pros and cons and ensuring that any strategy is aligned with budgets available and commercial objectives.

Get in touch if you would like to discuss your options…

Special thanks are due to Camille Terve and Benjamin Oakham for their work in processing and analysing the data sets from the EPO.

Emma works across all stages of the IP lifecycle from drafting and prosecuting patents to managing offensive and defensive opposition proceedings at the EPO. She is particularly experienced in the fields of photonics and Computer Implemented Inventions (CIIs). Emma’s opposition experience includes the management of large opposition portfolios and she regularly advises on wider IP strategies within contentious technology areas, both in terms of advising on patents that cause potential issues for her clients and also in helping her clients to build up patent portfolios that are robust against attacks from others.

Email: emma.graham@mewburn.com

Sign up to our newsletter: Forward - news, insights and features

Our people

Our IP specialists work at all stage of the IP life cycle and provide strategic advice about patent, trade mark and registered designs, as well as any IP-related disputes and legal and commercial requirements.

Our peopleContact Us

We have an easily-accessible office in central London, as well as a number of regional offices throughout the UK and an office in Munich, Germany. We’d love to hear from you, so please get in touch.

Get in touch