Taylor Dolezal of the Cloud Native Computing Foundation explains why the tech industry reveres this technical yet vital concept.

Forward: features are independent pieces written for Mewburn Ellis discussing and celebrating the best of innovation and exploration from the scientific and entrepreneurial worlds.

How alike are tech giants? At first glance Amazon, Spotify, Netflix, Uber, Google and the other digital behemoths appear to be originals in their space.

In product terms that’s true. Yet peek under the bonnet of these cutting-edge companies and each is spookily similar. So matching, in fact, that an engineer can move from any of the aforementioned companies and be ready to work at another within a matter of days.

Across the whole tech world you'll find replicas of the same tools and ideas at work, from retail platform Rakuten in Japan to Swedish telco Ericsson. This is the universe of Cloud Native companies. These are organisations which are built on a common set of principles, and most likely run identical, or very similar, software packages.

It is why anyone interested in building a world class organisation needs to understand the concept of Cloud Native.

“We talk about ‘Same team, different companies’,” says Taylor Dolezal, head of ecosystem at the Cloud Native Computing Foundation, known as the CNCF, and the ideal person to explain the remarkable power of Cloud Native ideas.

Taylor Dolezal, head of ecosystem at the Cloud Native Computing Foundation

“It's possible for an engineer to go from Google to Microsoft to Red Hat and the environments are very similar,” he confirms. “We have a community of 7.1 million people, which is larger than some countries.”

A roll call of CNCF members highlights the size of the Cloud Native empire: Airbnb, Apple, eBay, Google, IBM, Intel, Microsoft, Huawei, Oracle, Alibaba, Twitter and Samsung. It's not all tech companies, with the likes of Audi, Toyota, Volvo, Goldman Sachs, Lockheed Martin and Walmart also members.

The full landscape totals over 800 members with a combined market value of $21 trillion. That's larger than the combined annual GDP of all member states of the European Union.

“We have a community of 7.1 million people, which is larger than some countries.”

The CNCF brings these companies together and oversees the maintenance of the software tools they depend on. Membership can seem a little like a Masonic handshake in tech.

“Absolutely!” says Dolezal. “The community really is all about networking. Even at KubeCon [the flagship annual event] people come for that hallway effect, being able to meet these maintainers and people they normally wouldn't be able to see because we are distributed within our open source communities.”

A giveaway is the ship wheel logo of the CNCF's most important software tool called Kubernetes. During our interview Dolezal is wearing a cap with the Kubernetes logo on it. “I'll put it on my list to make a secret handshake or some form of identification,” he jokes. “Maybe you can shoot off a blue flare or something.”

What is Cloud Native?

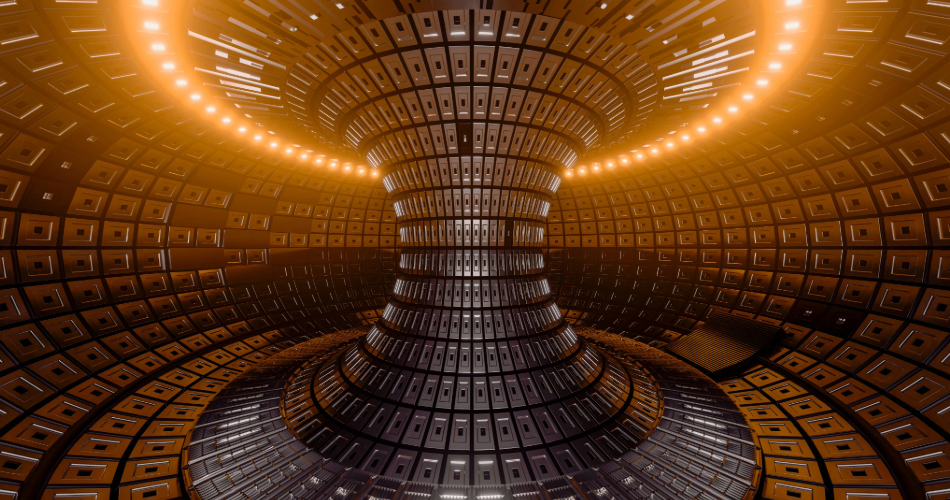

The basic concept of Cloud Native is simple. The goal is to build software that maximises the power of cloud hosting – third-party data centres which replace a company's proprietary data centres.

The largest cloud hosts are Amazon Web Services (AWS), Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure, Alibaba Cloud and IBM Cloud. Netflix, for example, is entirely hosted on AWS; it alone accounts for around 15% of global internet traffic.

Cloud Native companies do more than change their hosting location.

“When it comes to making things Cloud Native, it's a completely different thought pattern,” explains Dolezal. “The analogy I like to use is, it's like building something in wood and then trying to build something similar in concrete. They have different properties. Concrete distributes weight differently, it binds differently, and functions completely differently.”

Cloud Native software, for example, is built to expand or contract as needed. The cloud offers near limitless storage and compute power – even Netflix launching a new show can't overwhelm the sheer size of Amazon's cloud data centres. With the right set-up, a retailer experiencing a surge of custom on Black Friday can simply expand its software footprint as needed. When the surge dies down, the applications contract automatically to save money.

Cloud Native software is also astonishingly resilient, to the point of being ‘self-healing’. Rather than build single block applications, Cloud Native principles suggest splitting applications into autonomous chunks, called Microservices. A company might have dozens or hundreds of Microservices. Thus, a bank might put the cash machine functions inside one Microservice, and the loan book inside another. If one Microservice malfunctions the others run unaffected. Teams can upgrade their Microservice out of sync with others, making innovation easier and faster.

KubernetesPronounced koob-er-nett-ees, the term originates from the Greek word κυβερνήτης, Greek for helmsman or pilot. Kubernetes 1.0 was released in 2015, based on Google's in-house container management tool Borg. Kubernetes is also abbreviated to K8s, the ‘8’ representing the number of letters replaced. The CNCF maintains Kubernetes on behalf of the Cloud Native community, among other tools. |

Now things get a little technical. Inside each Microservice, software is packaged into discrete packages known as containers. These containers share an operating system, so are extremely fast to spin-up, and are also able to run on any hardware, as they bring everything they need to operate. In the software world, this versatility is highly prized. Furthermore, individual containers can be killed and replaced in a split second if they malfunction. This is the ‘self-healing’ concept. The tool which manages the process is called Kubernetes – a vital tool in the Cloud Native world. VMware, a software company, estimates 65% of large companies now use Kubernetes in production.

Can Dolezal explain Kubernetes? “The best thing is the Children's Guide to Kubernetes,” he says. “It's fantastic. The guide is free and online at the CNCF's website. The star is a giraffe. Honestly, it's the first thing I got my hands on to really understand what Kubernetes was. I'd read tons of articles and other things, but it wasn't until I read this book I really got it. I have the print copy behind me right now.”

Most people are happy to know simply that Kubernetes is the thing that controls the software containers. Make no mistake, Kubernetes is worth grappling with. It's a major reason Cloud Native services such as Netflix and Spotify rarely go down. Google developed Kubernetes, but it is considered too important for any single organisation to dominate, so in 2015 Google worked with the Linux Foundation to launch the CNCF to oversee its development. Kubernetes today is open source and the licence is free.

A diverse yet united community

The CNCF oversees a treasure trove of tools for its members. “We've got Prometheus, Opa, Jaeger,” says Dolezal. “One of my favourites is the incubating Buildpacks project, which allows folks to build container applications from their source code and run on their cloud of choice.”

It's also the case that there are multiple tools available for the same task.

“There's a phrase we use internally, that we aren't kingmakers. We don't pick winners. We try to encourage the community to come together and build the tools they need. If you look at the GitOps space, there's a project called Flux and a project called Argo. They are essentially doing similar things, but they've chosen different ways to accomplish that. Do we have a favourite? No, we help and encourage both of those communities. Then hopefully the competition makes them both better.”

It's a surprising feature of the Cloud Native tools that they are open source and developed in co-operation by supposed rivals. Developers from Amazon and eBay may well contribute to the same project. Neither owns the final product – the tools tend to be licensed under the Copyleft principles, such as the Creative Commons or GNU General Public Licence, which encourage the sharing of free-to-use, but hard to copyright, products. Kubernetes, for example, is distributed under the Apache 2.0 licence, which is defined as: “A permissive license whose main conditions require preservation of copyright and license notices. Contributors provide an express grant of patent rights. Licensed works, modifications and larger works may be distributed under different terms and without source code.”

“There's a phrase we use internally, that we aren't kingmakers. We don't pick winners. We try to encourage the community to come together and build the tools they need.”

Dolezal marvels at the pro-social nature of this co-operation: “The way it's been described to me, and I really like, is that we all get together for a big dinner and everyone jumps into the kitchen to help wash the dishes and clean up. It's not all put on the back of one person.”

The philosophy of open source produces better software – bugs are caught by multiple parties all working on a project. And open source software improves confidence in the final products, as no nasty surprises can be hidden away.

“We advocate for working in public and pulling people in,” says Dolezal. “If you propose something in your own company you need to pitch that in a way that benefits your organisation. With open source, the mindset is different. The question is how to make life easier for all the users. And whether other companies actually come in and help with the overall effort. We work together. You see a lot more trust in that model and within that sort of community.”

“The way it's been described to me, and I really like, is that we all get together for a big dinner and everyone jumps into the kitchen to help wash the dishes and clean up.”

The power of Cloud Native is now well understood in the tech world. The British entrepreneur Paul Taylor was introduced to the firepower of Cloud Native ideas when he went to work for Google. He recalls: “Like a sous chef who has learned in a great restaurant, I felt that after leaving Google, I was leaving with the recipe of how to build a great tech company.” He founded a firm called Thought Machine to build bank software based entirely on Cloud Native ideas, in an industry where they are rare. Thought Machine was valued at $2.6 billion at the last funding round.

The success of Cloud Native companies makes the CNCF an astonishingly influential and altruistic place to work. It's the nexus where the giants of capitalism come together to build tools for mutual advantage.

“It really is a joyful place,” says Dolezal. “All of us here have a history within open source doing something where, in a lot of cases, people aren't getting paid to do. There are rare exceptions, but this is their passion project. I'm able to work with all these people and have great discussions. Being able to see when someone doesn't understand the concept, and then see that spark light up behind their eyes, that brings me joy. That's why I do it.”

Why Cloud Native is so importantBy Michael Mueller, founder and CEO of Form3, a payments company and CNCF member that has raised $217 million over six funding rounds:

|

Leveraging the full power of cloud computing

James Leach, Partner and Patent Attorney, Mewburn Ellis comments:

“The cloud native approach is allowing tech companies to leverage the full power of cloud computing. I am looking forward to seeing what new services arise as more tech companies adopt this approach.”

Written by Charles Orton-Jones

James is a Partner and Patent Attorney at Mewburn Ellis. He has a wide range of experience in patent drafting and prosecution at both the European Patent Office (EPO) and UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) across a variety of industry sectors. James has particular expertise in the patentability of software and business-related inventions in Europe.

Email: james.leach@mewburn.com

Sign up to our newsletter: Forward - news, insights and features

Our people

Our IP specialists work at all stage of the IP life cycle and provide strategic advice about patent, trade mark and registered designs, as well as any IP-related disputes and legal and commercial requirements.

Our peopleContact Us

We have an easily-accessible office in central London, as well as a number of regional offices throughout the UK and an office in Munich, Germany. We’d love to hear from you, so please get in touch.

Get in touch