Rob Law, the founder and chief executive of Magmatic who make the Trunki product, said that the Supreme Court’s ruling in Magmatic v. PMS International Ltd would “create chaos and confusion” for those seeking design protection in the UK. This blog intends to offer some practical guidance for UK designers, and to ease some of this possible disorder and muddle.

The law

To start with, a brief recap of the law surrounding designs in the UK. There are two mainstream routes you can chose when looking to protect your design. Either you can apply for an EU-wide registered design (a so called Registered Community Design, or RCD), or a UK only Registered Design. Magmatic applied for an RCD, and asked the UK courts to determine if PMS had committed an infringement by producing and selling their Kiddee case.

In either case, a registered design protects the appearance of the whole or part of a product. For an article to infringe a registered design, it should not produce a different overall impression on an informed user.

However, when determining this, one must take into account the degree of freedom of the designer, when designing the allegedly infringing article. For example, if the design related to a telephone, the designer is restricted in that the telephone would probably have to have a speaker and a microphone which are an appropriate distance away from one another (ear to mouth).

Magmatic's registration

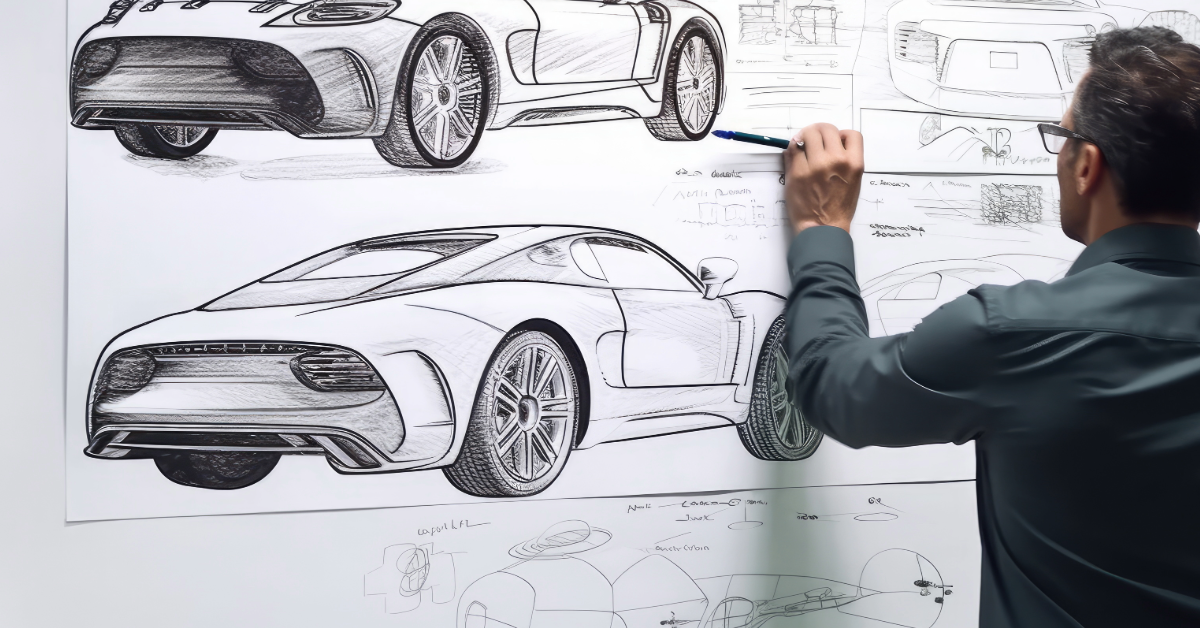

Turning now to Magmatic’s registration, they made use of computer generated images in their RCD as shown below.

Magmatic’s Registered Design

Notably, the registration clearly shows the effect of light on the surface of the product, as well as highlighting the difference in tone between the bulk of the case and its wheels.

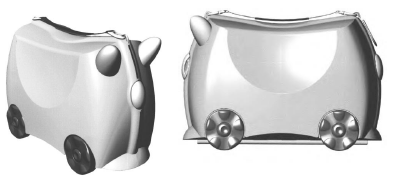

Kiddee Case

The Supreme Court paid a lot of attention to this difference. It is quite unlikely that Magmatic intended to highlight that aspect of their design when they prepared and filed the registration, however this (partially) allowed the Supreme Court to conclude that the Kiddee case (an image of which is shown above) did produce a different overall impression and therefore did not infringe.

What can you do?

So what can designers do to try and make sure their registered designs provide the protection they want? The first, and arguably most important, thing to recognise is that designs do not protect the idea of a product. Magmatic’s registration could not protect the idea of a sit-on suitcase. It could only ever protect the shape and appearance of the sit-on suitcase.

As a result, designers should look to produce representations of their design which are as ‘generic’ as possible. If one used the Kiddee case images to register a design, it would clearly be too narrow. There is quite a lot of detail in the design which help give it an individual character. Arguably, the lady-bug case produces quite a different impression, as compared to the lion case! Magmatic’s representation is quite a bit better, but as discussed above contains some features which provide a contrast which is not necessarily what you would want.

However, this ‘genericising’ (or broadening) of the design should be matched against the need for the design to be valid. To be valid, the design should be new – i.e. not exactly the same as a design known to the public – and it should produce a different overall impression on the informed user (the same test as discussed above with relation to infringement). So, let’s say that the new and ‘impressionable’ aspect of your design was the surface decoration of a tea mug. If the shape of tea mug was known, you shouldn’t register a design for that shape without the surface decoration being present.

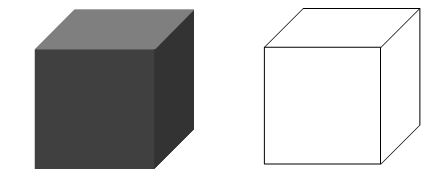

As another example, if your design was for a new mobile phone you should think about producing line-drawings of the design rather than relying on computer-generated images or photographs. These might produce differences due to lighting for example, which don’t fairly represent your design. As a very coarse example of how this might happen, look at the two images below for a cube.

The 3D model of the cube has been lit from the top, and so the top side looks a markedly different colour to the front or other sides. Whereas the line-drawing of the cube removes this ambiguity.

Other measures

Of course it’s very difficult to know with any certainty whether or not your design is valid. So what other measures can a designer take?

It is possible, both for UK registered designs and RCDs, to file a single application which contains multiple designs. This is a very cost effective way to have a number of registrations which vary in the protection they might offer. The Supreme Court made a point of mentioning that multiple designs can be included in one application, and that this should be an effective way to produce a ‘cascade’ of protection. To take the cube example above, a first design included in the application could be the line drawing as it is the broadest. Next, the 3D model could be included as a second design; it’s narrower than the first and so it’s more likely to be held valid. A further design to be included could be a more detailed representation of the actual product which will be sold to help protect against absolutely clear copying. The same approach can be used to protect independently different parts of a product and/or different variations in colour or other surface decoration in a range of products, for example.

In summary

To sum up, if cost is not a concern, you should look at filing multiple designs with varying levels of detail and to any variations in the design that you considered important. If you’re constrained by finances, you should consider what the most important aspect of your design is and try to make sure that that aspect is the focus of your registration, and not other features which might be present.

The “best” or most cost effective strategy for providing design protection for a product will depend very much on the facts of the case and the commercial importance of the product. If you want to discuss a particular case, then one of our registered design experts would be happy to help.

View the Magmatic v. PMS International Ltd Supreme Court ruling

Tom is a Partner and Patent Attorney at Mewburn Ellis. He handles a wide range of patent work, including original drafting, prosecution and opposition, particularly defensive oppositions, in the engineering, electronics, computing and physics fields. Tom also advises on Freedom-to-Operate, infringement issues and registered designs.

Email: tom.furnival@mewburn.com

Sign up to our newsletter: Forward - news, insights and features

Our people

Our IP specialists work at all stage of the IP life cycle and provide strategic advice about patent, trade mark and registered designs, as well as any IP-related disputes and legal and commercial requirements.

Our peopleContact Us

We have an easily-accessible office in central London, as well as a number of regional offices throughout the UK and an office in Munich, Germany. We’d love to hear from you, so please get in touch.

Get in touch