3rd June 2021 marks the 4th World Bicycle Day, which, in the words of the UN, recognises the “uniqueness, longevity and versatility of the bicycle, which has been in use for two centuries, and that it is a simple, affordable, reliable, clean and environmentally fit sustainable means of transportation, fostering environmental stewardship and health”.

Whilst across much of the world, the past century has seen the bicycle give way to motorised vehicles as the major method of transportation of people, it is clear that as we seek to combat climate change and manage increasing urbanisation, the bicycle provides a simple and cheap mobility solution that helps urban areas to de-couple population growth and emissions while also providing health benefits. Moreover, as the work of World Bicycle Relief highlights, in the rural areas of developing countries, the humble bicycle offers an affordable and practical means of transport, enabling many to access essential goods and services such as clean water, education and health care that would otherwise be out of reach.

The modern bicycle has come a long way from its naissance in 19th century Europe, and in this blog we take a look back over two centuries of innovation, eccentricity and intellectual property rights that have brought us the highly engineered and efficient bikes we have today.

The pedal velocipede

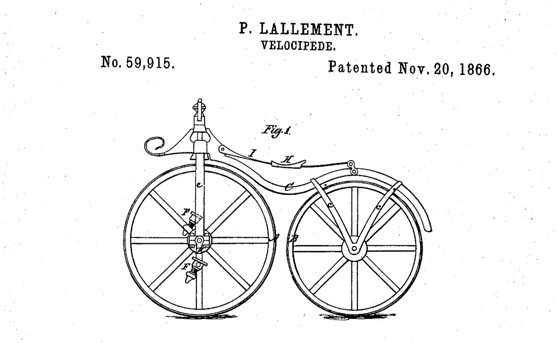

The origin of the very first bicycle, or velocipede as they were more popularly known in 1800s, is a contentious subject. However, the emergence of the pedal-powered velocipede can be traced back in the patent literature to the work of Pierre Lallement and James Carroll. Their US patent application in November 1866 for a velocipede with cranks and ‘rocking-treadles’ (pedals to you and me) attached to the front wheel’s axle kickstarted a golden age of bicycle development.

Figure 1: Lallement and Carroll’s Velocipede (Source)

If the idea of trying to simultaneously pedal and steer the same front wheel isn’t scary enough, the vertically aligned steering axis shown in the application’s figures would have provided some terrifyingly twitchy steering!

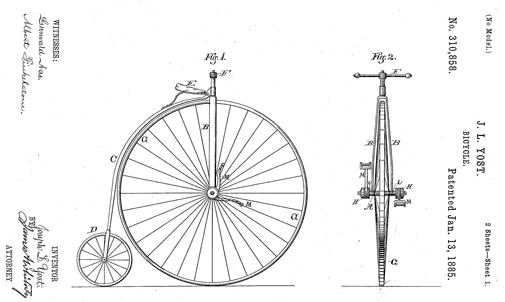

In the absence of any gearing system on early velocipedes and the desire for greater speeds, engineers quickly jumped on the idea of making the driven wheel larger and larger, meaning that for each turn of the pedals you travelled that bit further, quickly leading to the Penny Farthing in the 1870s.

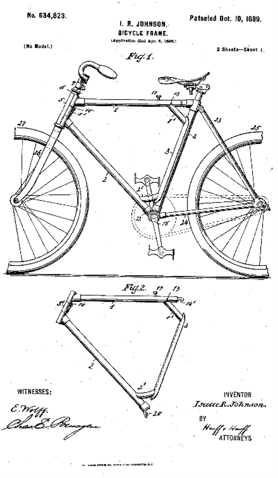

Figure 2: The figures for a patent relating to a penny farthing in 1885 (Source)

This decade also saw the patenting of another critical invention that would greatly improve the reliability of the wire spoked wheels these early bicycles were using: the tangentially laced wheel. Patented by James Starley of Coventry, these wheels used crossing spokes that extended tangentially from the wheel’s hub, greatly improving the stiffness and durability of the wheel in comparison to wheels using radially-extending spokes without any crossing.

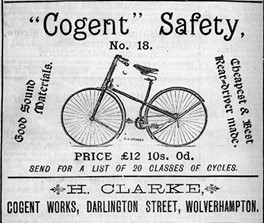

The safety bicycle

While the increase in speed achieved with penny farthings was welcomed by many, it also came hand-in-hand with an increased risk of injury. The position of the rider on a penny farthing, where they sit almost directly above the front axle, resulted in a propensity to be thrown over the front wheel when hitting bumps in the road! Many broken wrists and head injuries were the result.

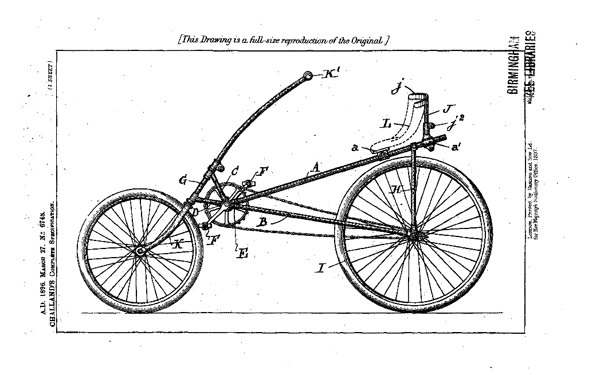

Figure 3: The original Safety bicycle, with the design principles on which almost all modern bicycles are based (Source)

It was in the 1880s that this was addressed with the invention of the safety bicycle. The critical development with the safety bicycle was the change from a direct-drive system, where the turning of the pedals directly rotated a wheel, to a chain drive system to the rear wheel. This allowed a suitable gear ratio to be selected and the size of the wheels to be reduced such that the rider was no longer balancing 5 feet up in the air and could easily place their feet on the ground when needed. The separation of steering and driving to two separate wheels also made the safety bicycle significantly more practical as a form of transport.

However, there was initially some resistance, as whilst the reduction in wheel size had improved the safety of the bike, the smaller diameter also made for a much bumpier ride. It was at this point that experimentation with suspension springs to try to address this began, but it was John Dunlop’s invention of the pneumatic bicycle tyre in 1887 (and his granted – but then subsequently invalidated – patent in 1889) that proved to be pivotal.

|

Figure 5: Figures form Challand’s patent application for recumbent bicycle (Source) |

The arrival of the first and second world wars then put many of these new inventions to the test, with all sides putting the bicycle to use, primarily in troop transport and reconnaissance. Bicycles specifically adapted to the needs of the armed forces, featuring reinforced frames and increased equipment carrying capacity, also appeared.

Post war to the present day

Following its invention in the 1880s, the basic design principals of the safety bicycle have largely remained present in most of the bicycles developed over the past century. Instead, innovation has mostly focussed on improvements to all the individual components that make up modern-day bicycles.

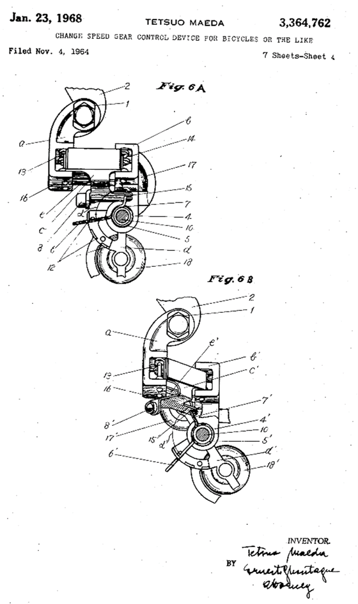

Figure 6: The much-revered Suntour Gran-Prix (Source)

It was only in the 1930s that bikes with multiple gears were allowed to be used in the growing European bike racing scene, and it was from this point on that Jean Loubeyre’s derailleur received a lot more attention. Lucien Juy, a French inventor, was a prolific patentee of bicycle gear shifting mechanisms and patented the first cable-operated derailleur (previous versions had all been lever-operated). This was quickly followed by Campagnolo’s patent for their much-refined Gran Sport derailleur in 1950 and Suntour’s slant-parallelogram rear derailleur in 1964. Suntour’s design was such a large step forward in derailleur design that many of its competitors eagerly awaited the patent’s expiry in the 1980s, before promptly making use of the design themselves.

More recently, hand-in-hand with battery and motor technology rapidly improving, there has been a resurgence in interest in electric bicycles, which many see as a key technology in the revolution in urban mobility that will be required as urban populations continue to grow and we seek to curtail our environmental-impact (see our blogs The rise of e-scooters - micromobility gains momentum and Intermodality: the future of transport?). This has been reflected in the patenting rate for inventions relating to electric bicycles, which has seen more than a four-fold increase over the past decade.

Re-inventing the wheel

While “re-inventing the wheel” is normally a put-down rather than something to aspire to, it is not something that engineers in the bicycle industry shy away from trying to achieve. It was recently announced that infringement proceedings were being brought by SRAM against Princeton Carbon Works over the wheels with undulating rim profiles for improved aerodynamics that both companies are producing, and for which SRAM has a related patent. Moreover, intellectual property rights in the cycling industry are no longer solely focussed on the physical components that come together to make a bike, with Trek Bicycles recently obtaining a US patent for a computer method for the optimisation of wheel rim geometry. Even if today’s bicycle innovations are more focussed on marginal gains than major revolutions, it seems that intellectual property rights are no less important to the industry today than they were in the heyday of bicycle development.

Rob is a patent attorney in our engineering and ICT team. Rob has an MEng degree in Chemical Engineering from the University of Cambridge. His masters research project focussed on three-dimensional analysis of particle-size segregation within granular avalanches using magnetic resonance imaging. During his undergraduate studies, Rob spent time working for Proctor & Gamble within their Baby-Care R&D Group.

Email: rob.walker@mewburn.com

Sign up to our newsletter: Forward - news, insights and features

Our people

Our IP specialists work at all stage of the IP life cycle and provide strategic advice about patent, trade mark and registered designs, as well as any IP-related disputes and legal and commercial requirements.

Our peopleContact Us

We have an easily-accessible office in central London, as well as a number of regional offices throughout the UK and an office in Munich, Germany. We’d love to hear from you, so please get in touch.

Get in touch